The study of genetics dates back to the nineteenth century, when Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian monk, pioneered the field. Between 1856 and 1863, Mendel’s meticulous experiments with pea plants demonstrated offspring display a combination of physical traits from both parents, thereby identifying the basic principles of genetic inheritance. Although he couldn’t figure out the “invisible factors” that determine phenotype (the observable characteristics of an organism), Mendel proved the inheritance of specific traits follows a predictable pattern through multiple generations of seed-grown plants.

Modern-day genetics is much more complex, but Mendel’s work still forms the foundation of agricultural breeding practices today. In fact, most of the commercially produced vegetables humans eat—with the ironic exception of peas—are the result of generations of scientific investigation into genetics at the DNA level, culminating in the development of stable first-generation, or F1, hybrid seeds that produce offspring phenotypically indistinguishable from the parent plants.

After decades of research and development, the advantages of growing food crops from F1 hybrid seeds are well established. Produced by cross-pollinating two genetically uniform parent plants, F1 hybrid seeds typically produce seedlings that exhibit “hybrid vigor”: higher survival rates, earlier flower development, higher yields, and resistance to some pests and diseases. Monsanto’s genetically modified F1 hybrid corn and soybeans are even resistant to herbicides the company manufactures.

But F1 hybrid seeds also have some disadvantages in the commodity crops world, including cost and a lengthy development cycle. (It can take as many as eight years to genetically stabilize a line of parent plants.) Additionally, F1 hybrid seedlings don’t breed true to type. Many are infertile, and those that aren’t produce seeds that generate offspring with an unpredictable combination of traits from the grandparent plants. Consequently, farmers must buy new seeds every year if they hope to reproduce last year’s harvest. For some commodity crops, that has led to a virtual hostage situation in the United States: Monsanto owns and zealously protects its patents on nearly 80 percent of the corn and 90 percent of the soybeans grown in the country. Farmers have no legal right to grow from seeds produced by the plants they cultivate. The same is true for the home gardeners who grow some varieties of tomatoes, cucumbers, broccoli, and melons from seed.

Cannabis, like most other commercial crops, has been grown from seed for thousands of years, and seeds remain a common propagation method for outdoor growers. F1 hybrid seeds are a relatively new phenomenon in the industry, having been introduced by Royal Queen Seeds in 2016 and still not widely adopted in commercial grows.

The other common cannabis propagation method is cloning, wherein a cutting is taken or tissue is cultured from a “mother” plant and grown into an exact genetic replica of the parent. Because clones are literally a piece of the original, cloning allows for the indefinite preservation of popular strains.

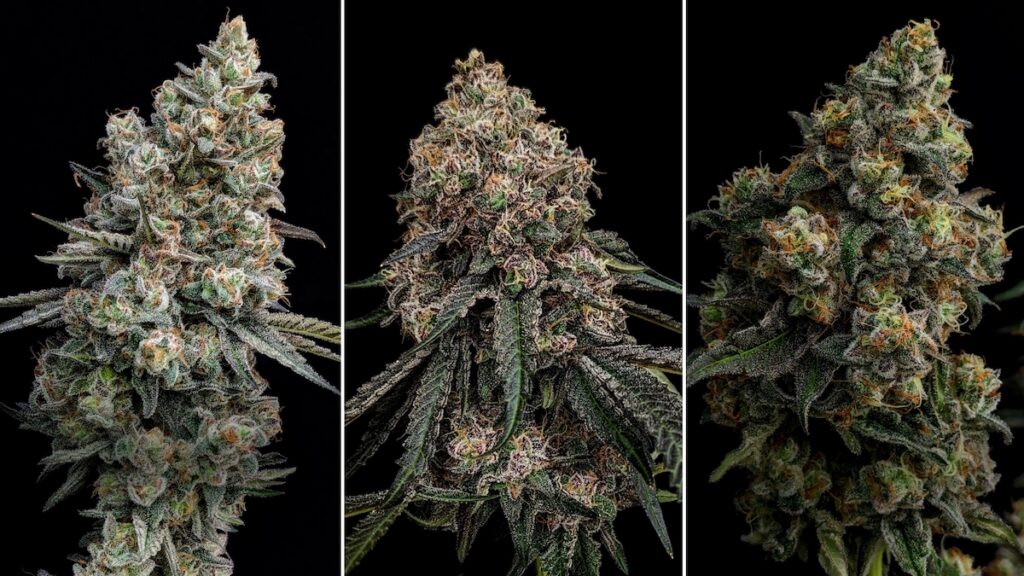

Both propagation methods have their proponents. Advocates for F1 hybrid seeds say they can produce plants that are identical to their parents but stronger and faster growing. They predict F1 hybrid seeds could replace clones as the dominant cultivation modality within a decade. But not everyone is convinced. Developers of popular strains currently grown exclusively from clones worry that genetics remains an imprecise science subject to, among other things, unintended mutations that could destroy their legacy. In addition, cultivators in challenging climates say seeds may not be efficient in all environments.

In praise of seeds

Because of their shorter growth cycle, cannabis plants grown from some varieties of F1 hybrid seeds allow cultivators to grow crops in climates where traditional varieties might not thrive or the growing window is limited by shorter seasons. F1 hybrid seedlings also can produce higher yields. For cultivators, this can result in greater efficiency: Multiple cycles and staggered harvests mean more crops can be grown on the same amount of land, which is particularly valuable in regions where space is limited and maximizing margins is crucial to profitability. In addition, because plant breeders carefully select parent plants with strong natural resistance to common pests and diseases, the need for chemical interventions like pesticides and fungicides is reduced.

And, like vegetables, cannabis F1 hybrids exhibit heterosis, or hybrid vigor. This makes them more resilient to environmental stressors such as drought and poor soil quality.

“Outdoor growers who grow from [traditional] seed often struggle with uniformity issues, [hermaphroditism], basic seed quality, and germination rates,” according to Phylos Bioscience Chief Science Officer Alisha Holloway. F1 hybrid seeds typically solve all those problems, she said.

From a cost-benefit standpoint, F1 hybrid seeds offer savings by eliminating the need to build and maintain a mother-plant room and nursery zone, freeing up valuable production space. Without a need for those areas, growers can repurpose the square footage for production of more high-value flower. And the cost-saving benefits don’t stop there: Growing F1 hybrid seeds also reduces pest management costs thanks to their genetic resilience. The streamlined process of F1 cultivation reduces both time and labor requirements, contributing to overall cost efficiency. Together, these factors can enhance profitability and operational efficiency.

Perhaps most intriguingly, F1 hybrid seeds allow varieties that are popular on the West Coast to be propagated in the Midwest, the South, and on the East Coast. Because seeds contain less than the 0.3-percent cap on THC allowed by federal law, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (begrudgingly) acknowledged they don’t fall under the Controlled Substances Act, regardless how much THC the plants they produce contain. Consequently, seeds are legal to ship nationwide; clones aren’t.

In contrast, maintaining newly cloned plants requires constant attention to ensure the clones are growing in a healthy fashion and, in the case of tissue cultures, the living plant material continues to divide. Mother plants can pass to their offspring—including daughter clones selected to become the next generation of mothers—undetected pathogens like hop latent viroid (HLVd), which has become such a scourge cultivators refer to it as “the COVID of cannabis.”

“People are still growing clones that are decades old,” said Phylos Bioscience Senior Director of Breeding Jared Reynbery. “It’s just a fact of nature that diseases are propagated, and the longer a clonal variety is around, the longer you have a mom stock of that clonal variety, the more likely it is to pick up diseases which are really hard and sometimes impossible to get rid of.

“Breaking that disease cycle is a really important reason for moving to seeds,” he added.

There’s an environmental component to the pro-seeds argument, as well: Seed growing is more eco-friendly than growing from clones. A PBS documentary, SEED: The Untold Story, found indoor cultivators grew approximately 22 million pounds of cannabis in the U.S. in 2017, primarily from clones. Some of the facilities the documentary studied consumed 60 million gallons of water each day, with each cloning module consuming as much electricity as twenty-nine refrigerators.

The case for clones

Not everyone is sold on the notion that F1 hybrid seeds will revolutionize cultivation. One particularly strong advocate for clonal propagation is Smash Hits Cannabis Director of Cultivation Greg “Chemdog” Krzanowski, who said the genetic consistency clones offer is “why a lot of people, myself included, like clonal breeding.” He maintains that even seedlings produced by breeding identical clones to create F1 hybrid seeds wouldn’t have the same appeal, nor would they carry the same legacy.

“For our clones, we’re looking for the same strains over and over that we can produce and grow to the best versions of those genetics and offer in our stores,” he continued. “We can’t grow a bunch of seeds for one crop, sell out of those, and then when people come to love that strain and want it again, they won’t get it if it’s all [grown from] F1 seeds or non-clone.

“For business, cloning is the only way to go, especially with popular legacy strains,” he added. “The clone is the true test of quality genetics delivering time and time again.”

Climate concerns and expense also are major factors in Krzanowski’s reluctance to embrace seeds, especially as he operates in Massachusetts. “Outdoor cultivation doesn’t work the same way in the Northeast,” said the man who created the original Chemdog genetics from seeds he obtained at a 1991 Grateful Dead concert. “We don’t have the same conditions and can’t fully rely on outdoor cultivation alone. There’s more cold in New England versus California’s warm, dry weather. It’s more humid out here in the fall, with dew and damp and cold mornings. All of that means we run a higher risk of issues during the grow.”

“And,” he added, “[F1 hybrid seeds] are expensive.”

According to Ian Justus, senior vice president of cultivation and operations at Connected Cannabis Co., one widespread concern regarding large-scale F1 hybrid seed cultivation is the slow rate at which F1 hybrid parents can be developed, as the initial work can take years before viable progeny are realized.

Justus also noted that although increased disease resistance is certainly an advantage of plants cultivated from F1 hybrid seeds, seedlings remain at risk of contracting HLVd, a highly infectious RNA pathogen. HLVd spreads through plant sap, contaminated tools and water, and insects migrating between plants. The viroid remains stable on surfaces for weeks and can lead to reduced yields, stunted growth, and fewer trichomes.

While Phylos’s Reynbery agreed any plant, clone or seed-grown, can become infected with HLVd, he pointed out the primary vectors for transmission are mechanical. Although HLVd has been detected on seed coats after as much as two years in storage, it’s unlikely the disease could be transmitted genetically.

In addition, although some infected mother plants may be asymptomatic, symptoms might show up in a clone.

“Clones get HLVd and get weaker over time,” he said, “whereas cultivators start fresh every time they get a seed.”

Near-term disruptor or long-term investment?

“The adoption of growing from F1 hybrid seeds is starting to take off,” according to Reynbery. “The first time we [created an F1 hybrid batch], we didn’t know exactly how it would go. Now we’re selling out some varieties and have to plan six to eight months ahead of time to produce more hybrid seeds.”

One of the barriers to greater uptake of the seeds is a lack of understanding about what they are and how they’re produced, according to Holloway.

“The community at large doesn’t understand that if you sow 1,000 [F1 hybrid] seeds, you have 1,000 plants that look identical, similar to if you took 1,000 cuttings, you would see 1,000 roughly identical plants,” she said. “We had to get over an educational hurdle in the community to really show that F1 hybrid seeds could be consistent, uniform, mature at the same time, [and] have great flower quality, even though each individual plant was grown from seed instead of from a clonal mom stock. The adoption of F1 hybrid seeds has skyrocketed as people learn about this uniformity and consistency we’re talking about.”

Justus believes the current F1 hybrid buzz may be just a bit early, especially given how the pace of the industry moves at such a fast rate. “It’s really hard to invest in a lot of these longer-term technologies with a ton of confidence, because the way the market shifts is pretty astounding,” he said.

“I don’t believe F1 hybrid strains will be competitive in the premium market in the next ten years,” he added, but he’s “very confident they’re going to be able to find some good F1 varieties in the next five years. The number of commercial flavors that one grower is expected to produce in this market is unheard of.”

Justus also noted the debate over short- and long-term benefits of clonal versus F1 seed cultivation methods is not limited to the cannabis industry. “There’s a ton of discussions ongoing today about this same topic in strawberries, as the strawberry propagation system is very challenging,” he said. “There’s no real competitive commercial seed varieties that can compete against the cloning of strawberries, so those [cloning] programs aren’t stopping. It just takes so much time to make seed varieties competitive.”

As far as next-generation crop science, he’s eyeing a different-but-related area. “The technology that really stands to shake up the cannabis industry is gene editing,” he said, adding the technology could make rapid progress in a clonally propagated crop. “It stands to create new chemical forms and flavors breeders have never seen through conventional breeding methods.”

He added, “I am not aware of any company significantly chasing this technology for cannabis yet, but I am sure it will be very disruptive in the future.”