As fires rage across the western states, as the pandemic shows no signs of slowing down, as the president admits he knew the virus was deadly but did nothing to stop it, as the nation is so divided some people think Black lives don’t matter, as the upper 1 percent gets richer and everybody else gets poorer, as mass shootings and gun violence continue unabated, as cops kneel on a man’s neck until he is dead, I am left wondering… How did this all go so terribly wrong?

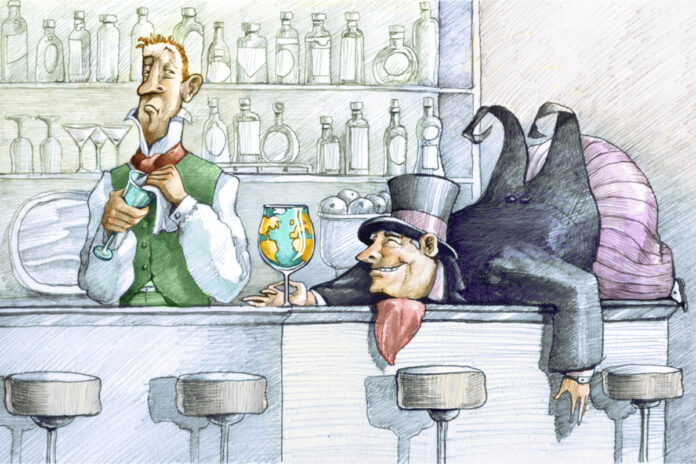

I blame Ronald Reagan and gin martinis.

A bit of history

After World War II, Japan was left in ruins. The allied forces led by the United States occupied the country and forced drastic changes. The entire country was reorganized, including its form of government, its economy, and its education system. Years of reconstruction were required to rebuild what was destroyed during thousands of air raids, especially the damage left by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

But by the 1950s, the former enemy found its footing and began transforming itself into a leading manufacturer of automobiles, consumer devices, and electronics.

At first, “Made in Japan” was a signal to American consumers that both quality and prices were low. But the folks in the Land of the Rising Sun were smart. They recognized they were playing a long game, and in the end their commitment to quality and cost-containment would win consumers’ favor. So, they manufactured to the highest standards of the time. They reverse-engineered all kinds of American-made products and then built them better and cheaper.

Post-WWII, American companies led the world in manufacturing. In 1961, General Motors had a whopping 45-percent share of the domestic automotive market. Ford had a respectable 29 percent. Chrysler had 10 percent. Together, the “Big 3” auto makers held almost 85 percent of the U.S. market.

Today, the picture is much different. GM has tumbled and now has only a 17-percent share of the domestic market. Ford has just 14 percent—half of what it once commanded. And Chrysler is no longer American-owned.

Globally, the picture for American automakers is even worse. Toyota is the world’s leading automotive manufacturer. Volkswagen is in second place. The Renault-Nissan partnership is in third.

And where is General Motors, once the biggest company (not just automotive company) in the world? Fifth place. Honda is in sixth, and Ford is in seventh.

Look to another product category and you’ll see similar progression: Kodak was once the leading film and camera manufacturer in the world and held an 85-percent market share of U.S. camera sales as late as 1976. Today, the five largest camera manufacturers are (in order) Canon, Sony, Nikon, Fujifilm, and Panasonic—all Japanese companies. Together, they hold a mindboggling 93.7 percent of the global market.

Kodak declared bankruptcy in 2012.

What went wrong?

By the 1960s, American corporations were fat and happy. They were king of the hill and thought no one could touch them.

They were wrong. The American corporate behemoths were satisfied with building cars that broke down and consumer electronics that were subpar, while Japanese manufacturers figured out how to make these same products better and longer-lasting at a lower price.

While American executives were lavishly rewarding themselves and their shareholders and feeling smugly secure that their world dominance would never end, their counterparts in other countries were busy working, investing in new and efficient factories, and committing themselves to research and development. As Japanese companies invested in new technologies, American executives enjoyed lengthy three-martini lunches at clubby restaurants with fancy food and inflated prices, often just a stone’s throw from their old, broken-down factories in Detroit and Youngstown and Pittsburgh and other once-mighty cities across the U.S.

American executives were on top of the world.

But in 1975, recession enveloped the American economy and imports began to eat away at U.S. companies’ once impenetrable market share, causing consumers’ sense and sensibilities to shift. People became less tolerant of American-made products that simply didn’t provide the same value as their overseas counterparts. American corporate hubris started the rapid decline of the nation’s manufacturing dominance and accelerated the corresponding loss of jobs that supported the middle class.

Then came Regeanomics.

“That to me is where our problems started, because it created a great amount of inequality,” said John Komlos, a former Duke economics professor and professor emeritus of economics and economic history at the University of Munich.

During a pre-pandemic lecture at Duke University, Komlos described a three-decade-long process that started with Reaganomics—which favored the rich—and continues to this day. In 1985, for example, a federal tax cut gave the top 1 percent a $350,000 windfall while the typical household received $3,500 and the poor received a couple of hundred dollars (all in today’s dollars).

George W. Bush continued to pamper the super-rich with his tax policies, and of course, Donald Trump infamously gave another huge tax cut to corporations and the wealthiest of the wealthy.

But the fact is, “trickle-down economics”—which Benjamin Lockwood, Wharton professor of business economics and public policy, said is characterized by the view that reducing taxes on the rich will benefit the non-rich—has never helped the average American consumer.

Art Laffer, the chief architect of Regeanomics, has been called “the world’s worst economist.” And to no one’s surprise, Donald Trump loves him. The Laffer economic policy has done tremendous damage to the American economy in the forty years since its birth. Each time the government has implemented a trickle-down tax policy, deficits balloon, the ultra-wealthy get even richer, and the average American suffers.

Perhaps not so ironically, the greatest periods of U.S. economic growth have coincided with policies that have raised taxes on wealthy individuals and corporations. In 1981, when the Regeanomics era was ushered in, federal deficits exploded, wages stagnated, and economic growth stalled. But in 1993, as the Clinton administration raised taxes on the wealthy and big corporations, economic growth exploded, wages went up, and the federal deficit turned into a surplus.

Then in 2000, the Bush tax cuts reversed this progress. Federal deficits once again hit historic levels, and wages began to drop. Then we saw the largest economic crash since the Depression and millions became unemployed.

The truth is, the toxic combination of American corporate greed and arrogance, coupled with tax policy that favors those who need help the least, have created many of today’s problems and inequities.

In a piece published in the traditionally conservative Wall Street Journal, Princeton economics professor Alan Blinder explained how tax cuts for the wealthy have made inequality worse. He pointed to a study that evaluated all federal, state, local, and corporate taxes and painstakingly traced records as far back as possible—all the way to 1913, when the Sixteenth Amendment created a federal income tax. The study found inequality has been rising for almost forty years, and working-class Americans now pay a larger share of their income in taxes than do the richest.

Let that last sentence sink in for a second.

“One can perhaps excuse Ronald Reagan, who couldn’t have known at the time of the 1981 tax cuts that it would produce more inequality for decades,” Blinder generously offered. “But by the time of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, George W. Bush’s team certainly knew that. And by 2017, when Donald Trump hammered the latest tax regressivity nail into the inequality coffin, virtually every sentient American knew that inequality was at a historic high.”

The result of policies that favor corporations and the wealthiest Americans is our great social divide has become deeper, the rich are richer while the poor are poorer, resentments are running higher and, ultimately, the nation’s status as a world leader is falling.

In the greatest of ironies, Donald Trump’s rank-and-file supporters are some of the very people who are most hurt by his policies.

I think I’m going to pour myself another martini while I contemplate that sad fact.

Randall Huft is president and creative director at Innovation Agency, an advertising, branding, and public relations firm specializing in the cannabis industry. While working with blue-chip companies including AT&T, United Airlines, IBM, Walgreens, American Express, Toyota, and Disney, he discovered what works, what doesn’t, and how to gain market share.