The indefatigable dean of cannabis law is keen to educate the public on the continuing toll of human suffering wrought by unjust marijuana laws and why the 2016 initiatives are so vital.

BY TOM HYMES | PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEFF FORNEY

For cannabis advocates, these may be the best of times and the worst of times. The mile high view reveals an industry gaining steady ground in terms of legitimacy, revenue, professionalism and investor interest, with states falling over themselves to embrace cannabinoids in one form or another. At ground level, however, it’s often a different story. Throughout the nation, people continue to be arrested by the thousands for mere possession, with thousands more facing felony charges for cultivation, distribution for sale, operating illegal dispensaries and other crimes. Even in a cannabis-loving state like California, a de facto war is being waged by law enforcement against not just the medical marijuana industry as it currently exists, but against a citizenry stuck within Catch 22-like grey areas of the law that even the lawyers and prosecutors are unable to define prior to a prosecution.

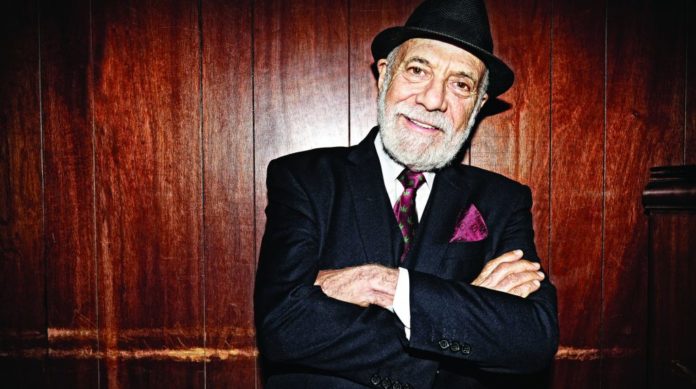

One criminal defense attorney whose articulation on the subject is matched only by his singular 46-year career as the dean of cannabis law is Bruce Margolin, author of the regularly updated The Margolin Guide to Marijuana Laws (available for download from his website).

73-years-young, with the energy of someone half his age, Margolin fights an unrelenting daily battle to keep his clients out of jail. Juggling 25-50 cases at a time out of a West Hollywood bungalow he’s inhabited for over 40 years, he and his associates and staff field a half dozen new calls a day from citizens and businesses desperate for help. Time is always of the essence, and a conversation with Margolin is often punctuated by incessant interruptions as he takes calls from clients or colleagues during exhausting days spent traveling from courthouse to courthouse.

But as hectic as Margolin’s law practice is, he also finds time to devote to his longtime role as director of the Los Angeles chapter of NORML, the pro-cannabis lobbying group founded in 1973. Margolin had started his own organization a few years earlier, but joined forces with the nationally-focused organization where he quickly became a fixture. It’s all part of the story of his initiation into the cruel realities of cannabis law as a “young pup” lawyer starting out in Los Angeles.

“The reason I got involved not just with defending marijuana cases but also changing the laws happened when I first became a lawyer in 1967 at the age of 25,” he told me as we drove from his home in Beverly Hills to the Ventura County courthouse where two cases awaited him. “I got a case involving about 25 kids who came to California and had one of these hippie houses in Hollywood. We didn’t worry about conflicts back then, but took everyone on and charged them $25 each. I remember standing in court downtown with the 25 of them all in a row, and it was great. But at the end of the day, one of them had to take the heat for the rest, and when it came time for sentencing I told the judge, ‘Your honor, my understanding of the law is that under the American Bar Association standards regarding punishment, the court should consider the intended wrong in order to punish. In my mind, there is no intended wrong with people involved with marijuana. They didn’t intend to hurt anybody, didn’t try to coerce anyone or take advantage of anybody. There is no basis to punish them, your honor, so how can you justify punishing this young man?’

‘Counsel, he broke the law.’

“So at that point I realized we had to do more than just be in the courtroom fighting these cases; we had to go outside the courtroom and change the law. And that’s how I got involved with the politics of pot, and I have been involved ever since.”

Naturally, Margolin has worked more than marijuana busts over the years, including a few murder cases here and there, and has had his share of celebrity clients, such as Timothy Leary, Christian Brando and Linda Lovelace; he has even run for political office several times over the years, including for governor in the 2003 California recall election and for Congress in 2012, efforts that resulted in respectable showings for Margolin and, as significantly, proved the viability of running on a marijuana legalization platform. Still, at the end of the day, it’s the nuts and bolts of cannabis law, as well as the troubling legal situation in Los Angeles and beyond, that consumes the man, as it would any civil libertarian.

“Anyone who’s involved in providing marijuana or edibles or any other products to a dispensary is currently in jeopardy of being prosecuted for a number of reasons,” he says when asked about the state of enforcement in California. “They will have to prove that they are a member of the collective—as collective members, they can provide products go the dispensary for purposes of aiding other collective members—but the Achilles’ heel for them is that it must be done for no profit, and profit is not defined by any of the court cases.”

Pausing for effect, he continues, “There’s only one case that refers to it that I’m aware of, People v Mentch (2008), which says that profit is a matter for the jury to decide. Generally, you look up rules regarding profit in the dictionary, where it says that profit is monies left over after overhead costs and operating expenses have been accounted for. That means defendants have to prove overhead costs and operating expenses, and also why the amounts they charge for product is relevant to what they charge. Unfortunately, we find many dispensaries that request arbitrary amounts for what they call ‘donations,’ which is the same as a sale. These amounts are often based upon arbitrary numbers rather than an accurate accounting that justifies the money requested. Therefore, even the dispensaries and co-ops are in jeopardy of having to prove that what they charge is relevant to what their overhead costs are.”

It gets worse, adds Margolin. “We don’t have any clear indication how to present these defenses to the courtroom. California Attorney General Kamala Harris had proposed to provide guidelines as required under Prop 215—which Jerry Brown did after its passage in 1996—but in 2010 she sent a letter to the legislature explaining that she could not come out with guidelines because she is unsure what the law is because of its lack of clarity in areas pertaining to profit, the operation of dispensaries and concerns about edibles. So all these things are left in a grey area that is very detrimental to people involved in the industry, as well as to patients and collectives that have to suffer the consequences of potentially being arrested and having to prove their defense in court, which can be very cumbersome and difficult, especially in this area of profit.”

Margolin adds that while many people assume that only illegal dispensaries are being targeted—and not the so-called “pre-ICO” dispensaries grandfathered in following passage of Proposition D in 2013—he cautions that the actual situation is far more nuanced. “When it first passed,” he explained, “the city put up on their website a list of names they considered to be compliant with Proposition D. That has been taken down, and when you ask the city attorney about whether they consider a specific dispensary to be legitimate, they say they don’t know, it’s up to the court. Well, how do you get the court to decide that unless you prosecute it? So they’re all in jeopardy of being in trouble; all in jeopardy of being taken down.

“It’s particularly bad for all of these people who provide dispensaries with products, including marijuana, because they don’t know if they are compliant or not, they can’t really determine that,” he continues. “And of course, there is also a lot of misinformation about the laws. Anyone who works at a dispensary, any landlord, any real estate agent providing the property, they are all subject to prosecution and do get prosecuted regularly. I am representing about 20 of these cases right now, including for landlords who didn’t have any idea that the businesses were not legitimate; they all appeared to be legitimate, but there is no way to determine if they are or not in advance of being prosecuted. It’s very unjust and a violation of due process, but there has not been any case so far that I know of that has resulted in a dismissal by the court under Proposition D, and there are no cases that I know of that have gone to trial and been successful in defeating the law, because the law doesn’t require any intent. Just doing the act is all that’s required; you don’t have to have intended to break the law.

“Typically,” he adds, “the fine in these cases is $1000 plus penalty assessments of $4000, in addition to terms and conditions that say you can’t participate in any collective or co-op, and also the place has to be closed down. That’s what’s happening, and in East L.A. they’re being prosecuted in one courthouse and the case load is unbelievable. It’s very burdensome to the court and very burdensome to the people being brought before the court.”

The authorities appear to be on a war path. He continues, ominously, “I went to a case last week involving Proposition D and spoke with the city attorney, and they said that once they clean up the numerous illegal dispensaries that still exist, which still amount to about 250, they’re going to go after the ones supposedly complying under Proposition D, to see if they’re obeying all the miscellaneous requirements, in particular what they call the live scans.” Live scan is a form of digital fingerprinting required of all dispensary managers under Prop D.

The situation is further compounded by the fact that California offers a patchwork of conflicting cannabis laws. “Each county and city has their own attitude about these cases,” says Margolin, “and California cities and counties can decide for themselves what sorts of laws they want to have regarding medical marijuana; they have complete autonomy to strike down any provisions they don’t want to comply with. For example, in Fresno County, they have a law that says you can’t grow marijuana there, period. There are other counties that have restricted dispensaries and co-ops, disallowing them entirely. In L.A. County, the city council put it to a vote that resulted in the passage of Proposition D, which limited dispensaries at that time to those that existed before 2007, and with other qualifications.”

We shift topic from enforcement to politics, in particular the all-important 2016 cannabis initiatives, about which Margolin, who is not a fan of Proposition D, has concerns related to the previous vote. Concerns, he adds, that are shared by California’s popular Lieutenant Governor, Gavin Newsom.

“I spoke with Lieutenant Governor Newsom about a month ago and his concerns are my concerns, that we will have too many cannabis initiatives on the ballot, which could water down the vote so that none of them gets over 50 percent,” he explains. “We could be in the same position we were with Proposition D; vote for all of them or we could wind up with none of them. But all of them might not be that good; we have to be careful about big Pharma or other big organization coming in with a lot of money to support a particular initiative that may not be in the best interest of the consumer. We want a free market here.”

He’s also concerned about protecting what he calls California’s “cottage industry for thousands and thousands of people for 30-40 years at least, so I am anxious to make sure that the initiative includes inexpensive licensing. For instance, with the CHHI initiative, I think it costs something like $50 to get a license to be a provider.”

CHHI is the California Cannabis Hemp Initiative 2016 (cchi2016.org), originally started by the late Jack Herer, which “calls for 99 plants per patient and up to 12 pounds of flower, and also includes the destruction of cannabis-related arrest records and the release of prisoners.”

Margolin wants to be able to support other cannabis initiatives as well, including the one by Reform California (reformca.com), a coalition of organizations spearheaded by Dale Sky Jones. The problem, he says, is that they have issued no language, basically telling the voters to trust them.

He adds that Reform California doesn’t seem to think that reforms such as releasing cannabis prisoners will be palatable to the voters. “But I think it will be,” he insists. “We already have laws in place for misdemeanor possession of cannabis that call for the destruction of arrest records after two years following probation, so it’s not outside the realm of possibility. I don’t think releasing the prisoners is such a terrible thing. Why should people remain in jail for a crime that is no longer a crime?”

In the meantime, he notes, “California legislators are scrambling to put in place regulations that will satisfy the federal government, because the fed’s view on medical and other marijuana laws is that the state’s must regulate them so there’s some control over the use, possession and in particular the transportation from state to state, which they feel they have a vested interest to prevent. My impression is that they are trying to get these regulations in place at the behest of Lieutenant Governor Newsom, because he’s probably putting in their ear the idea that we’re going to pass legalization in 2016, and he wants to have things ready to rock ‘n’ roll so we can comfortably deal with it when it happens.

Margolin has a million other things he wants to talk about—from reasonable oversight of edibles to ensuring that drivers are not unfairly targeted for marijuana DUIs that have no basis in science, resulting in convictions for people who are not driving impaired, and he certainly maintains a laser-like focus on next year’s elections, which he believes will be pivotal. There are others who fight on the front lines in Sacramento and Washington, D.C., whose expertise is in the schmoozing and negotiating that comes with high-level lobbying. But he sees his role as equally imperative, indeed, as the essential ingredient that could solely determine whether California truly lights the way for the rest of the country when it comes to legalized cannabis laws that make sense at every level of society and for all who want to participate.

It’s still all about educating the public about what’s truly at stake if the laws governing the use and sale of cannabis are not either eviscerated or improved. “I have my finger on the heartbeat of all the cases that are coming down and our concerns we have about legalization—and I myself, along with the judges, the appellate courts and everybody else, am left in a confused state because the laws are so unclear and have not been defined in many areas.”

His basic message to the populace remains consistent and compelling: “I think they have to first understand that cannabis is not legal, and that we are still incurring incarcerations, and they have to get into it. Two, they need to understand the same party line I have been repeating for 46 years; the irrationality of the laws, the unfairness and injustice, the waste of resources. We need to keep hammering away at those things until the masses absorb it, begin to understand it and then accept it. I think the tide is certainly turning, with polls indicating that 55 percent for legalization, but that’s not a safe enough margin for me.”

And the band played on…