Al Harrington, co-founder and chief executive officer at Viola Extracts Inc., never relied on his status as a former professional basketball player to pump his brand. Over the past decade, he built his business through perseverance and hustle, staying lean and mean and keeping a close eye on the bottom line.

In an industry that has failed to create any meaningful social equity or justice for people of color (POC), Viola Brands is notable as one of the first and largest African American-owned companies, with operations underway in six states. Only recently did Harrington take on his first institutional investment, but even as his new well-heeled partners stake a claim, there is no indication Harrington has any plans to change his core philosophies or vision.

Al Harrington’s bumpy, lumpy road to success

In a nondescript building near the Sunset strip in Los Angeles, Viola’s headquarters isn’t a flashy affair but it does reveal a distinct style and ethos—purple neon Viola signs scattered around the room, a bar stocked with Viola flower and extracts, a lounge area with leather sofas and a widescreen TV, and just as you enter, an artsy portrait of Harrison in a “Historically Black Cannabis” T-shirt. Above the reception desk hangs a purple-hued portrait of Harrington’s grandmother, the heart and soul of the brand.

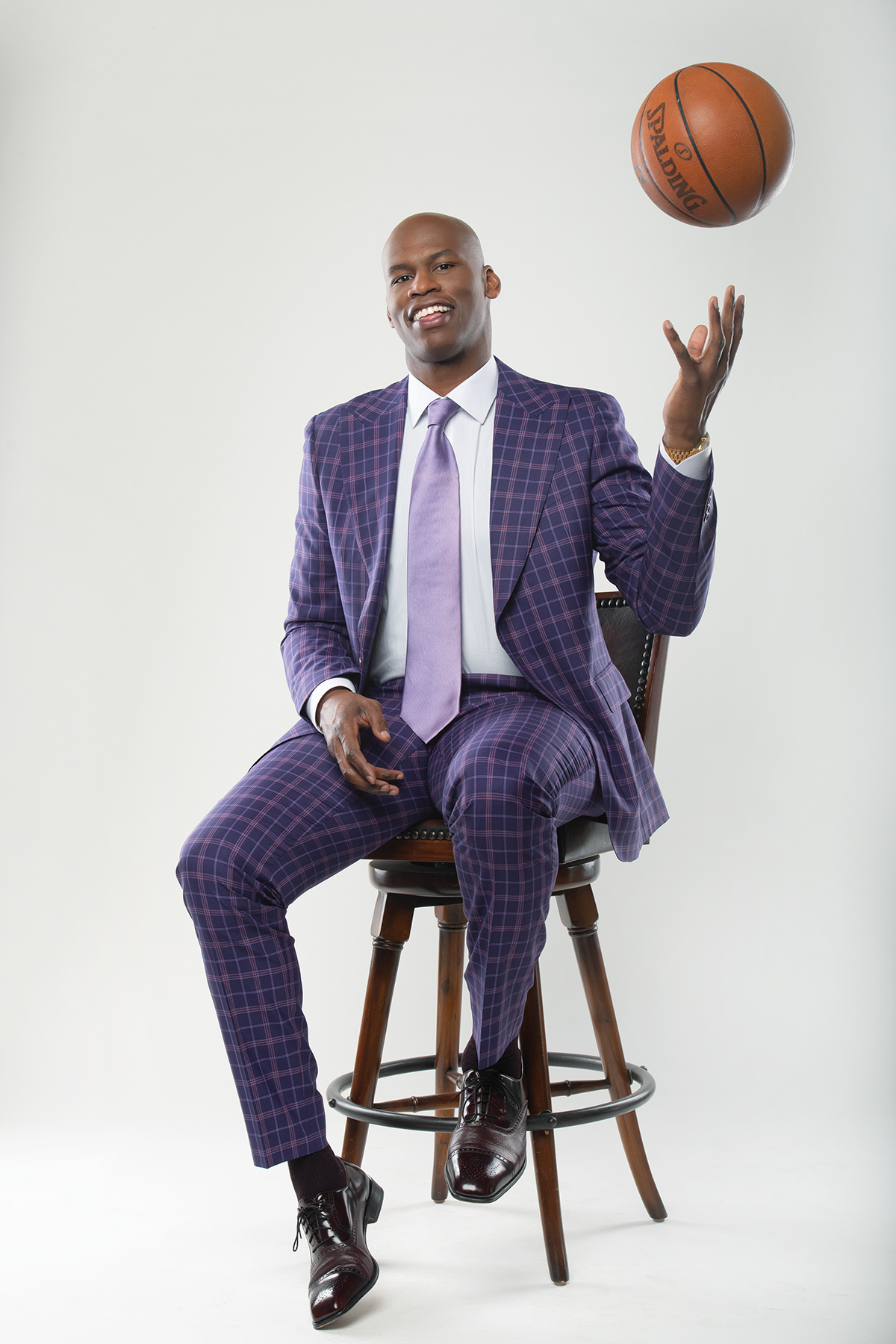

At six feet nine inches tall, Harrington is a commanding presence when he walks into a room, but his cheerful, gracious, and easygoing manner sets a relaxing vibe. For someone who was one of the top basketball players in the world in high school and played 16 seasons in the National Basketball Association, he is not one to brag about his accomplishments. He sees them primarily as the product of hard work and dedication, and these are the very same traits he brings to bear at Viola on a daily basis.

“I take the same work ethic into business, and that’s how I’ll be successful, and that’s how I have to work and what I demand from everybody,” he explained. “We’ve hired people—you know, marketing guys—and they came in with that prima donna attitude and it doesn’t work. If I need the garbage taken out, take the garbage out, bro. Whatever it takes to get stuff done around here, we get it done. That’ s how all my employees operate, I promise, because if they didn’t, they will stick out like a sore thumb.”

Drafted by the Indiana Pacers in 1998, Harrington was on the tail end of his pro career when he joined the Denver Nuggets in 2010. His decision to sign with the team turned out to be a game-changer in both his life and future business career, as the state was paving the way for the first recreational cannabis industry in the country under Colorado Amendment 64.

A newbie to cannabis and business, Harrington reached out to his friends for advice on starting a cultivation operation. One of his older teammates cautioned him, “You are in a cash business, so you have to deal with somebody you trust because they might rob you blind.” His cousin Dan Pettigrew was the only person he knew and trusted who had experience growing weed, so the two set off into the wild-and-woolly world of cultivation. They started their first grow under the medical marijuana system that had been in place since 2000.

“We started off small, and I’m happy it happened that way,” he said. “We took a lot of lumps and bruises, but better to take them small instead of having some major operation. We had forty lights and lost crops, got spider mites, got everything you can think of. It was a real learning curve for us.”

Back then, he noted, few professionally minded cannabis operators existed in Colorado, and more often than not the blind led the blind. “When I got my first attorney he was giving us all the wrong advice, so we realized that and whatever he told us to do, we did the opposite and we’d be successful,” he said, laughing and pounding his fist on the table. “It was just so crazy at that time, the way we grew the business. I had all these millionaire homeboys in tech and real estate, and I’d ask them for advice, but they didn’t know. We pioneered an industry through prohibition.”

Since its inception in 2014, Viola Brands has grown significantly in both size and scope and now has operations in Colorado, California, Oregon, and Michigan, with plans to expand into Arizona and Nevada in 2020. In all, the company operates nearly 100,000 square feet of indoor cultivation and extraction space and a six-acre farm in Oregon. Harrington estimates the company grows about 100 different strains to feed its product line.

“Each market is different, and no market really has the same strains,” he said. “In Colorado and Oregon, the reason we have so many is because we’re doing more concentrates. So, we mix this with that, and it gives us more variety with our SKUs.”

One of the reasons Viola Brands has focused on extracts is, well, Viola.

Grandma Viola

Harrington’s grandmother, Viola, stayed at his house when she visited to watch him play for the Nuggets. As she unpacked her bags, she took out her medications and placed them on the table, and Harrington said he was shocked at the variety of bottles and pills—about thirty in all—she used to alleviate symptoms from glaucoma and diabetes. That’s when he decided to sit her down and have a conversation…about weed.

“I got to Denver in 2010, and all they were talking about was cannabis,” he said. “The newspaper articles were describing all the benefits for people with epilepsy and seizures, so I was educating myself. Talking to her, I kept calling it cannabis, and she was just like, ‘What? What is cannabis?’ I said marijuana, and she says ‘Reefer?!’ She was like, ‘Oh my, all that’s going to do is make me hungry.’”

The following day, he recalled, her eyes hurt so much she could barely see, and she told him her medications were “hit and miss.” That was the day he convinced her to try cannabis. He thinks divine intervention played a role in her conversion. “That was God, because when you think about it, she was 79 years old, and since she was alive for the most part cannabis has been demonized. You know what I’m saying? If she was willing to try it, it was bigger than her.”

The results were dramatic and immediate. Viola said she was able to read her Bible clearly for the first time in years. “At that moment, it put me in this whirlwind and I really wanted to learn more about the plant,” he said. “It was just amazing to see cannabis help her have an experience like that, and it just inspired me to learn as much as I could.”

Now, when she uses her namesake products, Harrington said his grandmother prefers the oils because they don’t produce much odor and she is able to be more discreet when using her medicine.

Embedding social justice

Growing up in Orange, New Jersey, in the 1980s, Harrington’s impression of marijuana was similar to that of most black and brown people living in an urban area of the United States at the height of the drug war: FUD—fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

“The way I grew up, the war on drugs was on my doorstep every day, going down to the corner store and watching the older kids get stopped by the police,” he said. “In eighth grade, two kids in my homeroom class got locked up for having, like, nickel bags of weed in a locker. You would literally walk down the block and see a fiend in the alleyway and people would say, ‘If you smoke weed and do drugs, that’s how you’ll end up.’”

Beyond a business owned and controlled by African Americans, one of Harrington’s priorities for Viola is to promote ownership and equity for more POC in the cannabis industry. He noted POC in the U.S. have been involved in all aspects of the weed business for decades. Because they have been disproportionately targeted in the war on drugs, they should reap some of the rewards now that cannabis is legal.

“Our company is about trying to revitalize our community through cannabis, and it’s beyond just offering training and jobs,” he said. “We can create generational wealth, but jobs don’t create generational wealth. A job just sets you up for another job and another job and another job. Ownership is when you start to separate yourself.”

Harrington wants to create more effective strategies for bringing communities of color into the cannabis industry. In California, Viola identified entrepreneurs to support as they build companies and also helped them secure real estate to establish licensed operations.

“I think our people just have to wake up and realize in this situation it’s one of those things where you really should support brands that have people that look like you, because I really feel like cannabis is a way of reparations for the black community,” he said. “So, our goal as a company is to empower and uplift the community, to be a resource and an on-ramp for other black entrepreneurs to actually get into the cannabis space safely.”

Harrington’s message was on display at his headquarters in L.A. on a warm afternoon in October, as everyone who moved into and out of the building was African American.

Who is Al Harrington?

As a player in the NBA, “Big Al” was a versatile, athletic forward who had an all-around game. He was a steady shooter who could also bang the boards, played hard-nosed defense, and provided a spark off the bench. In 2012, he was among the top vote-getters for the Sixth Man of the Year award. As a CEO, Harrington is equally versatile and takes a hands-on interest in every aspect of his business. “You have to understand [profit-and-loss statements] and different things like that, because otherwise you are always relying on somebody else to give you information and you don’t really know if it’s truthful or not,” he said.

After running his business with a tight-knit team for so many years, Harrington recently decided he was ready to take on a significant outside investment and accelerate his operations nationwide. On a trip to New York in 2018, he called Jason Adler, co-founder and managing member of Gotham Green Partners, to catch up and talk shop. One thing led to another, and before long Harrington had a new business partner and a $16 million influx of capital.

Harrington said he met Adler several years ago, when the latter was building Cronos Group, a Toronto-based international cannabis company with a collection of large brands under its umbrella. Adler showed him some of the industrial-scale cultivation operations north of the border and opened his eyes to the possibilities of building an international brand.

“Adler is now one of those guys I can get advice from, even though I’ve been in the game longer,” Harrington said. “He’s seen it at a whole different level and looks at it from a totally different perspective than I do. “He [Adler] said, ‘I think you should raise more money, you should get more of a runway, you should do X, Y, and Z.’ And it made a lot of sense, you know?”

With the new funding, Viola acquired a cultivation, processing, and distribution facility in Adelanto, California, and is finishing the build-out of a 48,000-square-foot facility in Detroit. More than the money, though, Harrington views the relationship with Adler and his group as a key partnership that will pay dividends in other ways.

“We know we want to be a national brand, so we are constantly looking for strategic partnerships that we can align ourselves with to be able to do that,” he explained. “So, I just figured being in bed with a company like [Gotham], I can use some of their resources moving forward; Jason can connect me with some of the other companies he’s involved with. It’s one of those synergy kinds of environments where we really can excel as a company because of this relationship.”

Harrington’s game plan for the company thus far seems to be working: In 2019, Viola anticipates a nearly 300-percent jump over 2018’s revenue.

Harrington was a late bloomer in basketball and only started playing seriously as a freshman in high school. He quickly realized if he wanted to be successful in a competitive league in New Jersey, he would have to “live in the gym.” While his height and athletic abilities were obvious assets, he wasn’t a great shooter and spent weeks at a time improving his technique. By the time he graduated from high school in 1998, Harrington had been named USA Today’s National Player of the Year and a McDonald’s High School All-American. He headed straight for the NBA, something only a few other players had accomplished. He soon realized he would be dealing with some unexpected realities in the NBA’s fast lane.

NBA Marijuana

“My rookie year was the first time I saw pro athletes using cannabis, and they were some of the better players on the team,” he said. “That’s the first time I started to kind of wrap my head around it and realized what I was being told about [cannabis] was a lie.”

Today, twenty years after he started his NBA career, Harrington sees more and more players using cannabis to help them deal with the grind of seasons that can stretch from eight to ten months and put heavy demands on them both physically and mentally.

“I know what the grind of an NBA season looks and feels like, and it’s not easy and we’re constantly in pain. You know, nobody’s ever fully healthy,” he said. “They’re always giving us anything it takes to keep us out on the court, and a lot of those things aren’t very safe. When I look at my career for seventeen years, I took anti-inflammatories every day. I’m still young, but you know that may come back to bite me in the ass one day. But that was the position I was in at that time as the first generation of money in my family. So, if they wanted to hit me with a horse tranquilizer every day, I was gonna take it.”

The NBA banned cannabis use in 1999, even in states with licensed medical marijuana programs; the current collective bargaining agreement between the NBA and National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) runs through the 2024 season. Harrington said he has spoken to NBPA President Chris Paul about the possibility the union could push toward removing the medical marijuana ban, but it’s unclear whether the organization will do so.

“The way the NBA operates is, when collective bargaining comes up, usually both sides ask what they want,” he said. “I’m trying to educate the players to the point where they understand that they need access to cannabis, and I’m not talking about smoking herbal stuff. I’m talking about the creams; I’m talking about CBD and all the other cannabinoids that are in the plant.”

Harrington recently made his first play in the hemp and CBD industry with Harrington Wellness. The company’s first brand, re+PLAY, offers products including pain creams and capsules that combine traditional sports medicine with custom CBD formulations designed for athletes.

Despite the ban on using cannabis across professional sports in the U.S., Harrington said, “I see so many players use it now, and these guys are obviously the world’s greatest athletes. They use cannabis for their own medicinal purposes, and it’s just ridiculous that they have to hide that. The day is coming. It’s coming.”

When he talks to other NBA players and athletes about investing in the cannabis industry, he said they are afraid of losing their contracts if they become associated with a weed company.

“They still scare these guys,” he said. “I get it because, you know, number one, if you [use CBD], you have to make sure you do it with somebody you trust and who is handling business the right way. There are some serious challenges, and I’m very upfront with them about it. But I also tell them most pro athletes are black or minority and we do have some disposable income, so you can’t wait too much longer because there’s a window and it’s closing fast.”

As that window closes, Harrington wonders how many brands will be able to survive and how many of them will have POC or celebrity owners.

“There’s a culture in this business, and there are a lot of people whose lives were ruined to get us to this point,” he said. “Some of these celebrity brands aren’t going to win, because there is something authentic about cannabis and so many brands are throwing around money and women and don’t stand for much. It’s the brands you don’t hear about that are making crazy money. “Even the approach of a celebrity-driven brand—there’s not one that’s really successful,” he added. “[Viola is] not a celebrity brand. I just so happen to be the CEO, but I work my ass off and put my own money into this and don’t feel like I’m different from everybody else.”

[…] In January 2020, mg became the first publisher in the market to launch a digital edition of its print publication. The edition expanded the magazine’s readership by making mg’s award-winning content and design accessible anywhere on any device. Advertisers increased their reach with the opportunity to embed live links, video, and animations. Every month, production designers continue to find innovative ways to make the pages come alive—as they did by animating John Taylor’s featured photographs of cover subject Al Harrington. […]