In 2019, the vaping sector—including companies that specialize in oil extracts and cartridges—took a major reputational and financial hit in the wake of an outbreak of illnesses caused by tainted products. The entire industry felt the effect of declining retail sales and developed legitimate concerns about the long-term viability of the sector.

But don’t tell that to Sisu Extracts, which supplies about 20 percent of the California vape market with distillate, the honey-gold oil that registers between 88 percent and 92 percent THC and is the primary ingredient used to produce cannabis vape cartridges. In an industry slowly but surely being taken over by industrial-sized companies with deep-pocket Canadian and East Coast investors, it’s something of an anomaly to see an old-school, Humboldt County, California-based company commanding a significant segment of the lucrative oil market.

But co-founders Joe Wynne, Shannon Byers, and John Figueiredo had a clear vision and business plan when they started Sisu in 2017. Their goal was to produce a consistent, high-quality distillate, become a wholesale supplier to any and all brands, and pay farmers a fair wage. One of the company’s marketing sheets reads “Farmers. You Work Hard. You Deserve Better. Sisu Pays More.”

Early in its life, Sisu made an innovative business move that helped the company grow rapidly. By offering farmers 70 percent of the profits from distillate sales, Sisu developed contracts with 250 sun-grown cultivators who produce a wide variety of strains with complex cannabinoids and terpene profiles. For a farmer who harvests trim with 10 percent THC, a 70-percent split works out to about $165 per pound in today’s market. If the trim is higher quality, say 14 percent THC, each pound is worth about $230—not bad for a byproduct of flower production in a market where most full-season farmers receive less than $1,000 for a pound of high-grade buds.

Scaling up and branching out

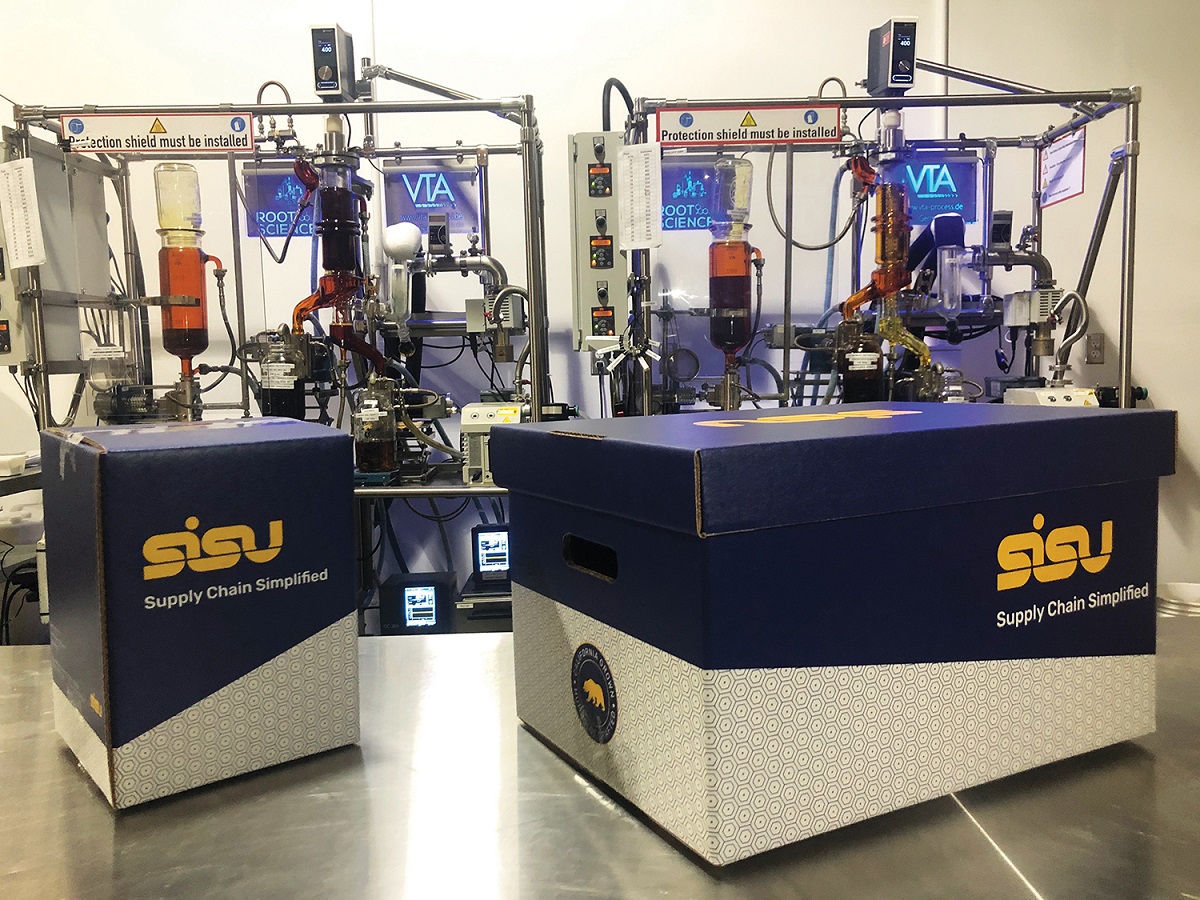

Byers, who serves as vice president of manufacturing, leads a team of more than thirty employees in the extraction lab, which processes more than 1,000 pounds of biomass daily. She began her career as a trimmer, later buying a small CO2 extraction machine and teaching herself how to produce high-quality distillate.

“None of [the co-founders have] a classic science background, but my mother, father, and stepfather were all engineers,” she said. “I do think that rubbed off on me a bit, and I’m a system builder and a problem solver by nature. So, it’s just been an autodidact kind of situation, teaching myself as I go and utilizing online and educational resources that are becoming more and more available. But I’m definitely self-taught.”

Early on with Sisu, Byers used butane as the primary solvent in order to produce high-end shatter, but she moved to ethanol because the substance is more efficient and better suited to high-volume production. Wynne estimates Sisu now produces and sells about 600 to 800 liters of distillate per month, an increase of about 300 percent over 2018’s level. The company serves twenty to thirty-five large clients across California.

“When we hook up with a large brand, if they can get [distillate] sold, we can get it made and my farmers end up getting paid,” Wynne explained. “And those brands hit a J curve. We’ve watched them go through that curve because the truth is, if you can provide a consistent product with a good marketing program at a great price point, people want that. This is selling weed in California. It is doable.”

A pivot toward purity

The recent sales decline precipitated by the vape-safety drama surrounding cannabis and tobacco products sent ripples throughout both industries’ economies. In cannabis, the likely culprit is black-market products containing vitamin E acetate and other adulterants. Vitamin E acetate is used as an inexpensive thinner but is not safe for people to inhale. An investigation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revealed nearly half the vaping samples tested nationwide contained the substance. The cannabis industry is holding its collective breath as politicians and regulators debate the matter and threaten bans and other extreme measures.

According to data from Seattle-based analytics firm Headset Inc., the vape portion of the recreational cannabis market in California fell for four consecutive weeks, from 31 percent in mid-August 2019 to 24 percent by mid-September. By December, data showed vape market share on the upswing, and Sisu’s founders believe there is a bright future for brands that are able to weather the storm.

“People do want this product. So, I think there is still great opportunity in the vape space for existing brands to do a good job to gain market share and then really be ready when the race across the states comes,” said Wynne.

Figueiredo, who serves as chief executive officer, added, “What we’re about to see is cannabis 2.0. There’s a lot of really well-funded companies and, just like what happened with tech in the early 2000s, you’re going to see the actual businesses that are running profitable, good businesses survive and make it to the next iteration.”

As a consequence of the vape controversy, consumers have become more aware of additives and diluents, including vitamin E acetate, that are used in vaporizer cartridges to liquefy cannabis oil so it vaporizes properly. Other additives sometimes used in vape oils include natural or artificial flavorings, including terpenes that are botanically derived from non-cannabis plants such as cloves (myrcene) and lavender (linalool). But as consumers learn more about the vape oil market, they are increasingly concerned about these additives and are paying more for ingredients and products derived solely from the cannabis plant.

Wynne explained vape oil manufacturers can buy botanically derived terpenes for as little as $100 per gallon, whereas the same terpene derived from cannabis can cost $40 to $70 per milliliter. In California, “live resin” cartridges—which use extracts produced from fresh-frozen flower and thus have a fuller, richer flavor—are becoming increasingly popular, even though they can cost two or three times as much as standard cartridges. “Most companies are moving toward both, if not all cannabis-derived terpenes,” he said, noting the practice is more prevalent in California than other states.

Responding to the trend, one of Sisu’s goals moving forward is to harvest terpenes from cannabis plants using a more efficient, high-volume process.

“Terpenes have never really been scaled, but that’s happening right now in a variety of ways,” said Wynne “We’ll be able to bring that product to market at a much closer delta to the cost of botanical terpenes, and then if you have the choice—instead of paying three times more you only have to pay 10 percent more for cannabis-derived—I think more and more customers will switch over. Because absolutely, in my opinion, the user experience is fantastically better.”

Expanding the brand

Because they work so closely with farmers, Sisu’s founders have developed unique perspective about the market and insights into potential future directions. Likewise, they’ve gained experience in so many aspects of the business that they aren’t afraid to take chances and explore new opportunities.

“The way we look at it is you want to be like pop music,” said Wynne. “We want to be a little bit ahead of the curve but not too far ahead of the curve, because there’s a bunch of proprietary technology we’ve seen people bring online and they’re still bringing online. But right now, we’re a leading-edge technology that’s also cost-effective.”

Another trend Wynne has noticed, resulting partly from high demand for extracts and retail emphasis on indoor flowers, is more outdoor growers focus on cultivating plants specifically for extraction purposes.

“We definitely have farmers throughout the entire state who grow full-term and are moving to an efficiency standpoint where they’re taking the tops of the plant for flower and then sending the rest in for processing,” said Figueiredo.

After Sisu established relationships with many farms, the founders decided to branch out into flower sales and sold more than $1 million in bud during the first month of distribution. The company recently expanded into a second location in nearby Eureka, California, to make room for a wholesale flower showroom and a butane extraction lab to develop more exotic, terpene-rich products for the high-end extract market.

“We’re kind of the brand behind the brand, and because of the strength of our supply chain, really the next thing along those lines is our flower,” said Figueiredo. “We’re really trying to make sure we’re the commodity supplier for the market and are a full-supply-chain solution.”

The strain name game always has been one of the more fascinating and mysterious parts of the cannabis industry. Until recently it was difficult, if not impossible, to identify the true origin and identity of any cultivar. Now that lab testing is a requirement to operate in the legal market, farmers are becoming more creative and savvier with their branding and marketing, stamping their unique genetics with new names. In the future, trademarks and patents likely will become commonplace.

“I think cannabis naming is about to take a major pivot toward the strange,” said Wynne. “There’s a lot of weird stuff coming down the pipeline as everybody tries to differentiate in the market, and people are trying to manufacture scarcity. Next year, there’s some really interesting names coming out that we’ve seen up here from some of our earliest-adopter growers.”

In 2019, Wynne and Figueiredo noted dessert names topped the charts, including Wedding Cake, Cherry Pie, and Vanilla Frosting. One of the more intriguing trends they predict for the near future is farmers adopting terminology from the wine industry. Don’t be surprised if cannabis aficionados are torching up OG Zinfandel and Sour D Sauvignon in 2020.

In Humboldt County and the Emerald Triangle, locals are fiercely proud of their heritage—and suspicious of outsiders and Johnny-come-latelies. Figueiredo’s family has been a fixture in the Arcata, California, community for decades, and that adds to the credibility of the company and might help Sisu seal a few deals with old-school farmers. Figueiredo’s family owned a chain of video stores for about thirty years, he said. Since farmers up in the mountains didn’t have reliable internet service, they would rent movies, and his family’s stores became known as the go-to for video rentals.

“The Figueiredos were embedded in the cannabis culture, because the farmers had to have their entertainment out on the hill,” he said. “It’s been fun hearing that story, because [farmers] always know my family. Because Joe and Shannon have been so deeply embedded in the industry, their credibility is really important. So, we have a mixture of both [old and new industry members], and that makes it fun.”