Of the many license types available to people interested in operating a cannabis business in California, the only one that cannot be combined with any other is for a testing lab. That is an indication of how essential the independence of the lab is to the viability of the regulatory scheme and the state’s ability to maintain control.

Labs are unique in other ways, as well. They traditionally and for the foreseeable future hold the keys to unlocking the secrets of the plant itself, and they require extraordinary amounts of money and talent to operate at scale and under International Organization for Standardization (ISO) certification, the latter of which is required for state licensure. It’s the cost of doing business on the up-and-up going forward. As instrumental as the labs have been in the development of California’s medicinal gray market, they became an indispensable player in the regulated economy, for better and worse.

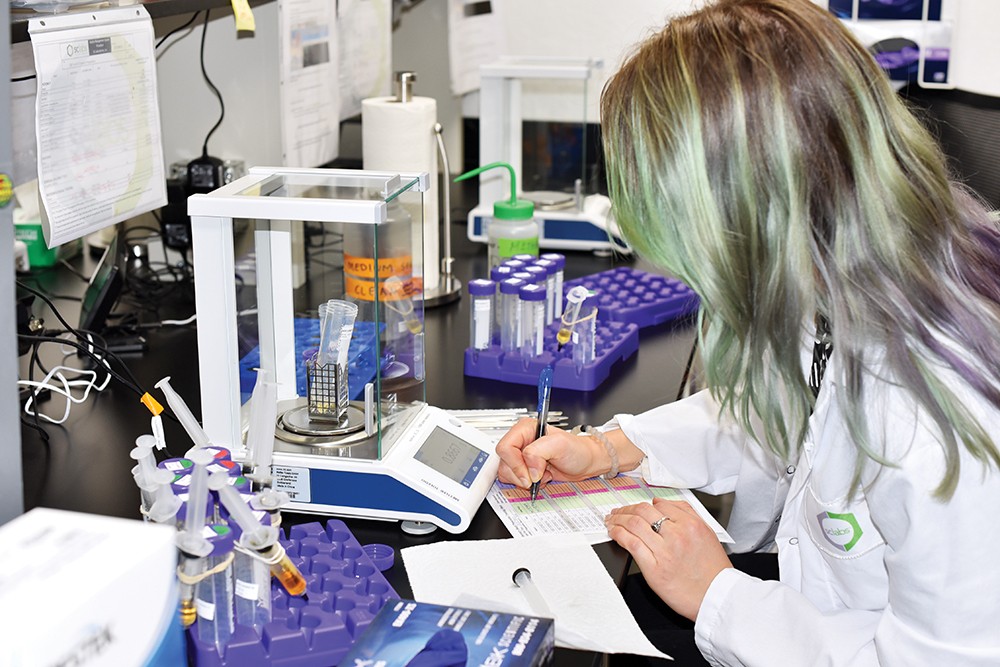

To get a sense of California’s readiness to engage its new regulated testing regime—which phases in via a three-step process of additional tests that commenced January 1 and will culminate December 31, with the METRC tracking system expected to be online by July 1—in early February we visited SC Labs and Steep Hill Labs, two of the industry’s leaders. At each location we found beehives of activity involving mostly scaling and training, and pools of positivity about the future combined with the sober recognition a lot of work still needs to be done if California is to avoid the worst mistakes made by other regulated states and take its rightful place as a world-class cannabis marketplace.

SC Labs

SC Labs’s main facility sits on a quiet cul-de-sac in a little slice of heaven called Santa Cruz, California. At around 9,000 square feet, the lab bulges with equipment and is in a state of relentless renovation and reallocation of space to make way for more testing capacity. Capacity, which will allow for faster turnaround of results, is the name of the game, the Holy Grail, and the only way SC believes it will be able to meet the testing and analytic needs of the largest cannabis-producing market in the world.

Josh Wurzer, SC Labs’s co-founder and president, is a passionate advocate for the business he’s in and the company he runs. During a day of frenetic activity, he graciously provided a tour of SC’s main lab and several smaller rooms, each of which was being assigned a unique and coordinated role in the evolving regulated testing process, and each of which was being fitted with new, often more powerful and very expensive instrumentation.

“One sample takes five departments to coordinate among themselves,” said Wurzer, who pointed out that everything had changed in the past few months and soon would change again. “In two months, none of this will be the same,” he said. “All of the office people are moving downtown. We’ve been in expansion mode, and as the year goes on we’ll continue to expand, including within this space.”

Teams of new employees filled the hallways on the day of our visit. “We have a lot of training going on,” noted Wurzer. “This time last year we had about thirty employees. Now we have all new employees, all new methods, all new machines, all new rules—just from six months ago.”

Outside, a small fleet of new vans stood ready to collect samples from licensed cannabis distributors throughout the state. “A distributor cannot give us samples for regulatory testing,” said Wurzer. “We have to pull samples ourselves. We go in with two-person crews, wearing full-body suits in sterile conditions, and will be presented with the entire batch. If it’s harvest flower, it can be up to a fifty-pound batch. We use randomized sampling techniques to collect a composite sample, collect a field duplicate sample as well, and then seal up the batch and bring it back here for testing. That batch cannot be released for sale until we send the cleared test results to METRC, saying it passed the test. If it failed because of pesticides, they can do a remediation step, but we have much more transparency into the actual batch that the test is being performed on.” While the lab cannot yet integrate with METRC, the state has asked all licensed entities to email test results and other documentation in the meantime.

Non-regulatory testing, used for research and development, also will continue to be offered as a paid service to clients in the space. “In R&D testing, someone sends or brings us a sample to be tested for their internal use,” explained Wurzer. “We don’t need to collect it or do nearly as much sampling.”

SC Labs formerly operated another testing lab farther south, in Santa Ana, but recently converted that facility for another use. “It’s now a field office, just like the Sacramento field office or the Santa Rosa field office,” said Wurzer. “We’re working with a huband-spoke model now We’ll have people doing far-flung runs to Southern California and Sacramento.”

As the company scales, the pace of regulatory sampling remains steady, if slow “Right now, we’re only doing about a hundred samples a day for regulatory compliance, but as the year goes on that will increase drastically,” said Wurzer. “Our goal was to hit January 1 with all the compliance tests required through July 7—which we didn’t find out until November 15, so that was a task in and of itself—have the tests prepared, and then build capacity throughout the year.”

Increasing capacity is essential. “Turnaround time is a big consideration for us, philosophically,” noted Wurzer. “We’re only going to accept as many tests as we can do, so we can keep our turnaround time to a minimum.”

Of course, all this testing comes with a high price tag. “For one pesticide test, I have to run a test on one machine and have it analyzed, and then run a test on another machine and have that analyzed. Each machine costs about half a million dollars,” said Wurzer. “You need a million dollars to do your first pesticide test, and then residual solvents are the same thing.” Of course, that amount does not account for the professionals doing the analysis, all of whom hold graduate degrees.

The costs will, of necessity, be passed along to businesses already squeezed by the price of legalization. “Costs may go up 50 to 60 percent,” said Wurzer. “I think we’re around $600 for the Category 1 and 2 sample, through July 1. It amounts to about 1 or 2 percent for cost control and safety, which I think is reasonable. We understand the burden falls heavily on the little guy, but we don’t think the cost of testing should put anyone out of business.”

A year from now, however, costs and thresholds will rise again. The final panel, which kicks in December 31, includes nine tests, including for heavy metals and micro-toxins, and will cost almost $1,000, according to Wurzer. “We probably won’t be the cheapest lab, but we will be competitive.”

According to co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Jeff Gray, SC Labs, which also operates in Oregon, is poised for growth. “We’re all blessed with greater opportunities at this moment in that regulation does a number of things, including allow us to invest in our business in a way that we know long-term those investments are safe,” he said. “That’s why you’re seeing so much capital flow into the industry. It’s a balance of risk and reward.

“The demand for lab services prior to regulation was really by the good actors, who represented a small percentage of the industry,” he added. “The number of labs servicing the sector were few because there really wasn’t that much there. But all that has changed. About thirty labs applied for licensing. I couldn’t have named ten last year. People are seeing the opportunity. What’s different about our sector and other sectors in the cannabis industry is that the demand for our services so far outpaces supply that we are not going to be subject to the predatory practices of larger companies. There are not enough companies, including even when the big companies come in, to do all the testing necessary to supply the market. It’s not about how many labs there are. It’s about how much capacity is necessary.”

The going will be rough at first, he added, especially the possibility of bottlenecks leading to supply shortages. “Let’s say thirty million pounds of cannabis are produced in California,” he said. “I don’t know if it’s accurate; I would guess it’s more, but if you use that number there will be 8,000 to 10,000 tests necessary per day. But they have now changed the harvest batch size, so divide that by five. Still, it’s seven days a week and just raw flower, not concentrates, and it’s only regulatory testing, not R&D. The need for testing is extreme, and the need for quick-turnaround testing is very extreme. It’s going to be challenging for people to keep up.”

There is another problem. Because of the demand, “you will have labs operating in the market putting out a subpar product, and no one will know the difference. It’s easy to tell great flower from dreck, but it’s not easy to tell good testing from bad. And there are people saying, ‘I need correct and credible science,’ and others saying, ‘I just need to pass.”‘

This also raises the question of testing priorities, and whether smaller distributors or small operations doing their own distribution will find themselves out-leveraged and stuck at the end of the testing line. “We’ve been working in this market for six years, and we’re from the cannabis industry,” said Gray. “We’re not trying to be leveraged or be part of something that creates leverage over the small participants in the industry. I don’t think it’s fair, but it’s not up to me. I’m not the fairness police. We have a group of clients that we’ve served historically, and I’d still like to be able to service them. The industry is here based on these early pioneers. They are a part of this industry and have endured the ups and downs, and we would like to think that we are loyal to those clients.

“We still have market dynamics,” he continued. “The way it works for business is that there are economies of scale that have to be reached. If I drive out and collect samples, I can collect 100 at a time or I can collect two. It works to my benefit and cost perspective to collect 100. What we are trying to do over time is limit the proportionate space within the laboratory to be able to serve a greater number of clients rather than have two giant companies we serve. I don’t think labs should be used as a tool to leverage a distributor’s power over cultivators.”

That same optimism and sense of purpose extends to the state. “The great thing about California is that we were the first to go medically legal, and there were no regulations while the other states put regulations and an organized system in place,” noted Wurzer. “Initially, that was annoying—because we were going to other states that were setting up things the way we wish we had them here—but in the end we were able to learn from their mistakes. And I think California and Oregon have got it the most right in terms of the regulations that affect labs—and quality control in general.”

Gray said he and Wurzer like the spot their company now occupies both fiscally and in terms of relationships. “Thankfully, almost all our equity is founder’s equity,” he said. “We’ve managed to remain profitable and reinvest money into the lab every year. Our path forward in the future is to improve our services. We like the focus of serving California and Oregon, the markets we’re in. Beyond that, SC Labs is interested in expanding, but not just in terms of the number of labs we operate, but the range of services we are offering. We come from the cannabis industry. We’re cultivators.”