Reggie Gaudino, PhD, is a fascinating combination of pure intellect and passionate impulse, a scientist of rigorous discipline happy to chill with a fatty, a man of the mind perfectly at home within the complicated topography and sociology of the cannabis industry. It’s been four years since he arrived at Steep Hill Labs, a published genetics researcher with eighteen years of intellectual property experience “writing, prosecuting, and managing patents and patent portfolios in fields as diverse as software and telecom to biotechnology and molecular genetics,” per his bio. He took on two heady job titles—Vice President for Scientific Operations and Director of Intellectual Property—and in the intervening years, in addition to his official duties, Gaudino sounded a constant refrain reminding the industry to guard intellectual property or risk losing it. The warnings, which I first heard a few years ago during one of Green Flower Media’s first series of streamed industry talks, remain dishearteningly germane today as the number of cannabis patent filings increases monthly.

“Nothing’s happened, not a damn thing, and the patents keep coming,” a frustrated Gaudino said in April. “The patent I was talking about [during the Green Flower Media presentation] that would be so detrimental to the industry was issued. It was a utility patent on a strain of cannabis, couched in a breeding-process patent, but that’s the thing—you can’t just look at a patent title and get anything from it. Unless you look at the claims, which people never do, you don’t understand what the patent is for.”

Gaudino knows whereof he speaks. He likes to read patents, a “hobby” that has given him rare insight into how they work.

“A plant patent gives you control of the plant itself and only the plant itself,” he said. “Typically, a plant patent is for something that is clonally propagated, which fits very well into how we do things in the cannabis industry. You go to a dispensary and see the clones there; that’s clonal propagation. Plant patents are good for that.

“Utility patents provide much broader protections than plant patents,” he continued. “If you get a utility patent on a plant, not only are you protecting the plant itself, but also the seeds and any products made from them. You’re taking your claim a step farther by saying the plant has unique properties—chemical output or unique genetics—and these properties are good for something else. That’s where you get the utility part.”

But this also is where the breakdown in cannabis patents occurs. “The entire plant patent foundation is built on a paradigm where everything is well-characterized and/or proprietary,” explained Gaudino. “Because of that, when you do a cross between a mother and a father, you end up with a new product that has bound parameters. A stabilized or true-breeding male or female has a repertoire, so when you put them (the stabilized or true-breeding genetic donors) together you’re going to get an F1 hybrid, which is the first generation from two well-characterized plants. The problem in cannabis is that nothing is well-characterized, and everything is a mishmash.”

While strains have traditionally been bred mostly to produce high THC, the industry does have some genetic lineage history to lean on. “Cherry AK was bred with this and it gave us this,” said Gaudino. “Great, but Cherry AK was an F1, and it wasn’t even a stabilized F1, but a mishmash, a hybrid. Someone had a bunch of seeds and found the one they liked and clonally propagated it, so it’s got no stabilization and is truly like something found in the wild.

“When you try to patent something like that you have a problem, because a patent is predicated on knowing the genetics or the combined chemical output,” he added. “Well, if you don’t really know and you haven’t had it characterized, how do you then offer a utility patent that protects the seeds?”

All of which raises a question: Why are these cannabis patents issued at all?

Doug’s Varin

Amanda Chicago Lewis made the problematic patent in question infamous in her taut August 2017 article for GQ magazine, “The Great Pot Monopoly Mystery.” She raised the specter of Monsanto-like patent arrogations underway even before the industry was federally legal. Lewis asked of the secretive patent applicants in her subhead, “Who are they? Can they be stopped?”

Gaudino, who is mentioned briefly in the article, said the issuance of a patent is an end in and of itself. “The presumption is that if it comes out of the patent office with a number on it, it’s a valid patent,” he said. “What has to happen is that someone has to have the time and the money to challenge that patent. Do I think it’s challengeable? Yes.”

That said, he acknowledged that the “mystery” patent was well-written. “It’s a damn good patent, but it’s a patent that cannot stand because patents for plants are built on a number of assumptions, including that they’re true breeding, from stabilized strains, and that they represent a well-categorized and well-defined genome. That does not exist in cannabis,” he stated. “The problem becomes that it may be a great patent, but the underpinning foundation of the patent is complete dogshit because we don’t have stabilized varieties. Almost everything is an F1, and we even use the term F1 incorrectly.

“In true agricultural genetics,” he continued, “an F1 is the first filial seedling population of two well-defined parents. Strain A and strain B give you F1 A + B. You can then follow the genetics in that offspring, because you know the definition of the parents. We don’t do that in cannabis. Instead, we take a female and four or five different males, throw them in a room, and see what we get.”

The first of the patents in question, of which there are now five, was issued in 2014 to a company called BioTech Institute LLC. According to Gaudino, BioTech consciously focused on cannabis strains that have both THC and CBD, which were not grown in abundance at the time the patent was filed.

“In cannabis culture, people generally want to get high, so THC-dominant strains were the ones important to people,” said Gaudino. “[BioTech] has no patents targeting THC-dominant strains, because they knew the industry would turn on them. But there were not a lot of people making THC-CBD plants back in 2012 and 2013. [BioTech] saw that arena and filed specifically on those things. They also took a strain that someone else gave them—Doug’s Varin, which Steep Hill had identified, and informed Doug of its uniqueness—incorporated it into their breeding program, and tried to file a patent on it, too.”

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejected Doug’s Varin but issued the other utility patents despite their deficiencies, Gaudino said. “They looked like good patents in the agricultural industry,” said Gaudino. “They were written in a way that they had the structure and feel of a proper patent.”

Gaudino shook his head at the thought. “Here’s the reality,” he said finally. “There is a claim out there for a hybrid cannabis plant making at least 3 percent THC and at least 3 percent CBD, and there is another version that says there is a BT/BD phenotype, which just means that it has an active THC synthase and an active CBD synthase, so it just has to make both. There are no lower limits or upper limits. The additional part of the claim that made it sound good to the examiner was that the patent included a terpene profile that was myrcene-dominant and had at least 1 percent terpenes. But if you are growing cannabis and you cannot make 1 percent terpenes, you shouldn’t be growing cannabis because cannabis plants make at least 1 percent terpenes. To the examiner it looked like a limitation on paper, however, and claim structure is all about limitations.”

Gaudino is not surprised the patents were issued. “The problem is that the cannabis industry is new in terms of patents, and there probably is not a single person working for the patent office who has grown cannabis in their life,” he said. “They have no clue that any cannabis plant makes 1 percent terpenes. They have no clue that if you are growing a THC or CBD plant, that if you cannot make 3 percent THC or CBD, you should not be a cannabis farmer. They simply don’t know that.”

A similar phenomenon happens in every new industry, he added, and often it takes years for the situation to play out, with bad patents issued and enforced in the meantime. Enforcement currently is not possible in cannabis because weed remains federally illegal. That will not be the case forever, though, and Gaudino fully expects there to be interest in the BioTech patents.

“Things could move very quickly,” he said, referring to the end of federal prohibition. “Once that happens, these patents could be phenomenally valuable. Who has the most to gain? Someone with deep pockets who will be able to keep anyone from challenging them. What will happen is that someone like Dow or Monsanto will try to snap up this company to get these patents. I fully expect the company that owns these patents will be looking for a buyer, but maybe they will turn around and donate them to humanity and put them in the public domain.

“But the fact they have not done it after this many years means it is unlikely to happen,” he added.

What sorts of cannabis plants will be covered by the infamous patents? “All the plants that make both THC and CBD, all the hybrids,” said Gaudino. “Anything that might be ‘medicinally useful.’ Go figure.”

Deeper dive

Gaudino, who checks for new cannabis patent applications every six months, said there are many new ones every time he looks. “The number goes up by about 200 applications every six months, a very steady increase,” he said. “When you look at the demographics of where these patents are coming from, a lot are from outside the United States. There are a growing number coming from within the U.S., but now there is a trend with non-traditional companies patenting into the cannabis space. We’re starting to see ozone treatments and other technologies that were applied elsewhere and are now improvement patents for use in cannabis.”

A world of pain still awaits the cannabis industry if overbroad patents are permitted to proliferate, but as fate would have it, Gaudino himself may influence how this story plays out. The scene is right out of a movie. Earlier this year, at the mid-winter session of the American Intellectual Property Lawyers Association (AIPLA), Gaudino presented a talk called “Challenges to Achieve Patent Quality for Cannabis Plants.” The presentation claimed the immediate attention of the all IP attorney’s attending the event, including one who submitted the material to the USPTO and another who wrote a blog post on the subject.

Within a week, Gaudino was contacted by the patent office and asked to present to the B/C/P (Biotech/Chemistry/Pharma) committee at the USPTO. The presentation he sent to the USPTO was titled “Accidental Infringement.” Without warning, the presentation was postponed by the USPTO, which Gaudino believes was unprepared for a presentation with that title, since you cannot have patents that can be accidentally infringed.

“It must have been a bit of a shock,” said Gaudino, who has a solution to the cannabis patent conundrum if only the USPTO is open to revising the way it assesses cannabis patents.

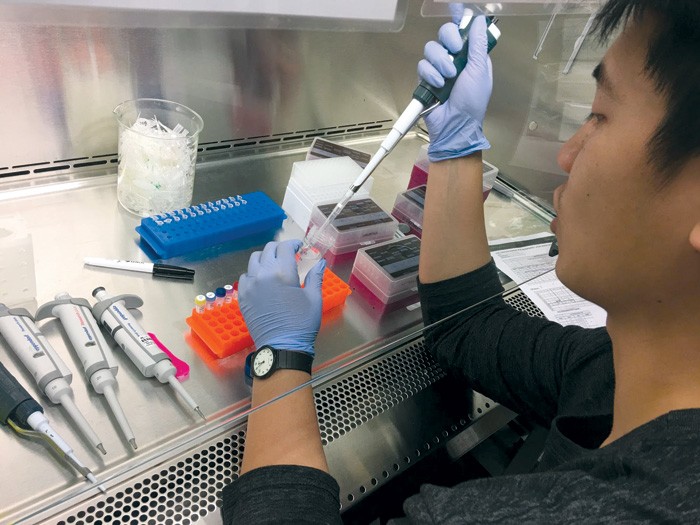

“What we see all day at Steep Hill are products that are called the same name, that presumably have identical genetics, but which come out with completely different chemical profiles,” said Gaudino. “The different growing conditions affect different systems in the plant. Genetics plus environment equals phenotype. That’s why, if you specify the genetics and you specify a set of growing conditions— which is not what is required in the patent record normally—now you’ve locked in one phenotype, one chemical output. That’s how you could have many people going after similar genetics and coexisting peacefully. You can require that they do a deeper dive into the information—tell us how your genetics are unique from someone else’s genetics. You need to show it and define the conditions that gave you the output you are claiming.

“The first step has happened,” added Gaudino. “[The USPTO] heard there is a problem and latched onto it immediately after hearing about my talk at the AIPLA meeting. I got a call a week after I gave the talk, so they are definitely aware of it.”

Despite the interest by the USPTO, Gaudino is not holding his breath that change will result. “There are very few companies in the world that do both chemistry and genetics on cannabis, and Steep Hill is one of them. In fact, we may be one of the only companies that does both,” he said. “The fact that there is a decent amount of data that we can associate with these properties is going to be very important to the industry and to the patent office, and I would hope they understand the message and adopt it.

“I understand from my data that the only way for the equation to be zero sum is if you define all of the pieces,” he continued. “You can’t just say, ‘I’m claiming a chemical profile,’ because you could have different genetics that get you to the same spot. And you can’t just claim genetics, because what if someone finds a unique nutrient formulation and applies it to those genetics and it produces a unique chemical profile? Do you automatically get his thing? So, these things cannot peacefully coexist, and there has to be a way to define it better. That way is using genetics and the environment, which locks in a phenotype.

“However, having been a patent practitioner for the past twenty years, I think something like that happening is unlikely, and if it does happen it will not be anytime soon. The muck and the mire keeps getting deeper.”

In the meantime, he said, the industry needs to get wise to the requirements of patent law. “The scary part about the cannabis industry is that any clone you can buy from a dispensary shelf right now is already open-source,” he said. “There are no patent rights for anything that has already been offered for sale.

“Dry flower is different,” he continued. “By selling the bud, you don’t ruin your rights. But you cannot patent clones internationally if they have been sold, and if they have been offered for sale for more than a year in the United States, they can’t be patented here. It doesn’t even have to be a signed deal. If it’s a public offer, the clock starts ticking. The only people who might be able to save their stuff are people who have not yet released it for sale.”

Licensing deals and appellation control hopefully will provide much-needed protections while the patent situation works itself out. “But licensing deals only work if you have not done what everyone else has done and put your cuts on dispensary shelves,” noted Gaudino. “You have to have the discipline to develop your unique strain, and only give it out to you, you, and you in licensing deals. If it’s seen anyplace other than there, one of those places screwed up.”

Expanding the global footprint

Steep Hill Labs spends a fortune on research and development, which Gaudino said is core to the company’s mission to add to the industry’s body of knowledge in tangible ways. “One of our projects is to be able to develop everything—by which I mean the ability to develop markers for breeding, not just for THC, CBD, or terpenes, but for anything,” he explained. “One of the quests is to augment all the minor cannabinoids and terpenes; to have them expressed at a higher level.”

The company also is involved with some collaborations in Israel, where Gaudino recently visited. “They have clinical trials for things like epilepsy, and they also have a monumental cancer-screening program where they are taking different strains, making extracts from the strains, and testing them against a battery of eighty cancer cell lines,” he said. “They take the strains and apply them to each of the cell lines to see what happens. Some kill everything, some kill nothing, and some kill specifically. The ones that kill everything are great, but you can’t do anything with them because they kill everything. The specific ones are the ones you follow. This is what is going on at a very high rate of speed now in Israel.

“The purpose is to create something called a genome-wide association study, which is taking the phenotypic data—the morphology, chemistry, color—and mapping it by meta-analysis to the genetics. We have a lot of whole genome sequences.”

Steep Hill’s vast amounts of data will be of immense value to agricultural and pharmaceutical companies looking for specific applications, but it also will be part of a larger study that overlays cannabis genetics and human genetics. “This is ultimately where we have to go, because everyone’s cannabinoid system is a little bit different, which is why people respond differently to the same strain. This is the next level we are working toward and let me tell you, if you think there is intellectual property now, wait until you get to that point.”

As we were going to press, Steep Hill Labs, which last year expanded its testing services to include every Canadian province and territory, announced an impressive expansion of its global footprint with a bevy of new international licensing agreements. “The licensee for Steep Hill Canada will expand their testing umbrella to include Mexico, Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom,” according to a company statement.

For Gaudino, the expansion just means more of the same. Now Chief Science Officer, he remains in charge of all research and development and intellectual property initiatives at Steep Hill, and he is more than up to the challenge.

“I have a very exciting job,” he said.

The online version of this article contains corrections and clarifications made after the print version (June 2018) went to press.

Comments are closed.