Red Antler, named for the fastest-growing cells in the animal kingdom, is a brand-building agency that focuses on startups. In fact, the company often works with company founders before they even have a product. Cofounders Emily Heyward, who serves as chief brand officer, and Chief Executive Officer JB Osborne started the Brooklyn, New York-based company in 2007 with a vision of working with founders from the start to ensure every client company’s identity is baked into its DNA.

The pair says the kinetic cannabis sector appeals to them because its evolving laws and geography require flexibility and creativity. Consider, for instance, the client with the clever name who couldn’t concisely say what was in the can. Or the company that struggled to raise capital because it emphasized the “Wow, dude!” factor rather than its professionalism. With cannabis still illegal at the federal level, Red Antler also anticipates a shakeout as mergers-and-acquisitions opportunities and funding sources contract.

In addition to running the business, Heyward is the author of Obsessed: Building a Brand People Love from Day One. Red Antler has nearly a dozen cannabis or CBD clients, a small but growing percentage of a sprawling client list including buzzy brands Casper, Allbirds, Thredup, and Oova.

The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Let’s start with a basic misconception. What is the difference between marketing and branding? When asked about branding, a lot of companies respond, “I have a name, logo, color, and website.”

Heyward: Branding is not a logo, it’s not a tagline, it’s not your name. Those things are important, but they are not expressions of why you ultimately matter.

So at its best, branding is more than just establishing an identity. It’s establishing a relationship expectation.

Osborne: Right.

What are some of the branding issues unique to cannabis? When consumers walk into most adult-use dispensaries, there is a cacophony of products, but they all look very similar. Sour Diesel is available from many brands, but there’s no way to tell them apart unless you already know what you are looking for. The ubiquitous seven-pointed leaf says “weed” and nothing more.

Heyward: There is not nearly enough differentiation or clarity happening right now among the different brands. Ideally, we reach a standard from the brand perspective where you are not looking for Sour Diesel. Instead, you’re looking for the new release from the brand you love, right? Because otherwise, whatever we’re all peddling is just generics. It’s like orange juice.

Osborne: A lot of brands are trying to be all things to all people. I think there’s a unique dynamic in this space. The demand is there, and it seems like whatever you put into a store, it’s probably going to sell. That’s especially true right now, because there is a newness, an excitement about having access. And I think it allows companies not to focus on building a brand and still be able to sell products. But I would argue this is a short-sighted strategy, because this category is going to see growth at a pace unlike anything else we have seen in recent decades.

Adult-use cannabis is now legal in eighteen states and could be legalized at the federal level someday, but not anytime soon. You are used to working in rapidly evolving industries. Is chaos attractive?

Heyward: We thrive in chaos. We are very accustomed to working in categories where the rules are still being written and we are having to adjust as we go [in order] to be nimble and flexible. It demands creativity, and we love that challenge.

It’s not just cannabis. We work in a lot of very complex categories that are highly regulated, from healthcare to insurance to [financial technology]. These are sectors where what companies are allowed to sell can vary from state to state. They are not all that different, but obviously cannabis is its own beast.

Osborne: It means you have to go into something assuming there is no perfect tool, because you’ve got to create a set of parts and then navigate.

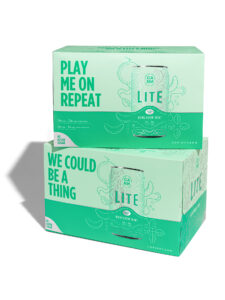

Restriction can foster creativity, and the cannabis industry has plenty of both. You helped develop the marketing phenomenon CANN, a THC-infused sparkling water. Officially, the product is only referred to as a social tonic, not a beverage.

Heyward: I think beverage and drink are not words that work very hard. We’ve worked with CANN since before they launched, helping them create their initial brand and packaging. We helped them evolve. We had a really fun social campaign where, as you are probably aware, we were not even able to name what the product was. That was a fascinating creative challenge. I think it was a great example of a scenario where constraint actually led to creativity, which I always believe to be the case.

It was a blast. Around the 2020 holidays, we created a campaign that CANN was all about a feeling. A strategy for the campaign was about getting people to consider swapping cannabis for alcohol in holiday-related social situations. We created a series of videos that just evoked a warm and fuzzy feeling, and the campaign actually performed really well because it got people intrigued.

Osborne: We really leaned into the notion that this is a social drink, like, this is something you’re going to take to a party, bring to the hostess, and you’re going out dancing. This helped us overcome any misconceptions. People don’t want to worry a drink will make them overly dosed, and we tried to convey this in the packaging.

How did people know know what the product in the videos was?

Osborne: They didn’t. It was just intriguing.

I watched a young man celebrate his birthday on YouTube, where he geeked out on the CANN can itself for about five minutes. I don’t know if he even tasted it. “You can see the fun packaging, there’s lots to look at,” he said, describing the line drawings on the can. He was even fascinated by the fancy pull-top.

Heyward: The packaging is usually the most visible part of the brand and sets up an expanded experience.

When should a business consider rebranding as opposed to just a refresh or facelift? What do you do when the company grows in distribution and sales? When is it enough to just remodel a company’s identity?

Heyward: My analogy is it’s like a breakup in a relationship. By the time you’re thinking about it, you’re probably past that point. It’s a really big process to rebrand, so the conversation usually is not even coming up unless there’s a really good reason.

The typical scenario we see is the initial brand was not set up to scale and grow. You don’t go to market with a brand that worked for a specific moment in time. Not thinking about how the business ultimately needs to scale is a huge mistake. To be successful, you have to start with strategy, audit the existing brand, anticipate how your brand will grow, and perform a reality check on the marketplace. And then, ideally, it’s a reimagining.

Sometimes we do help businesses rebrand because, you know, the category shifted or they realized they have an opportunity to go after a different target audience. It’s always emotional. In most cases, the baby step is not a good idea. Don’t have this conversation again in a year.

How does the branding process differ between business-to-business and business-to-consumer applications?

Osborne: We’ve done a lot of B2B in non-cannabis categories, and I’d say the difference is less than people think. There’s still a human on the other end having to make a decision. Truthfully, with B2B it’s actually even more complicated, because there’s usually multiple humans who have to weigh in on the decision. The brands that do the best in the B2B space are making their brand simpler and more compelling.

Heyward: Regarding B2B, we don’t see a distinction in branding itself, but the difference plays out in where the brand shows up, which audiences you are trying to target, and what types of tactics or messaging will be most effective. Seeing [B2B and B2C] as separate often can lead to making the wrong decisions and avoiding necessary risk.

So, I have to ask about MedMen, which I don’t think you’ve worked with. Would you care to comment on the rise and fall of a company with such strong brand recognition? The founders positioned the chain as a store for grown-ups, “the Apple Store of weed.” They even wowed investors on the Canadian Securities Exchange.

Osborne: We haven’t [worked with MedMen]. That’s a company that differentiated itself very quickly. MedMen created a lot of noise, which then means they have awareness. But they also had a lot less conversation with customers.

Heyward: I’ll say this: When I’m visiting [Los Angeles], it has historically been easier for me to go to MedMen because I already know what I’m going to get there. Sometimes I want a level of predictability versus trying to seek out the cool corner dispensary where I have no idea whether I’m going to be welcome or whether they have a selection I want. MedMen is less interesting, but it’s reliable.

How can a brand do damage control? What might a company do in the future when there’s another fatal vape crisis or a new study finds THC does more damage than alcohol?

Osborne: That’s the industry, not the product. Most often, what we’ve seen is a product launches and it works, so demand sometimes far outpaces supply. And it’s a pretty common start-up challenge. I’ve worked with companies like Allbirds and Casper, where the challenge for the business becomes whether you can make the product at the pace people are ordering it. That’s common in young businesses, because you’ve got limited funds and you have to produce a quantity before you know the market.

What about scaling up? We are talking about cannabis, but I also was thinking about craft beer. Microbrewers usually start as a beloved neighborhood brewery and, if the product is successful, InBev scoops them up and they lose their cachet. Goose Island started as a brewpub, and now you can buy the brand in grocery stores.

Heyward: That’s a great comparison. I think it’s the same with coffee. That sector has similar challenges as cannabis in that you have aficionados who are very interested in knowing the best of the best. That’s why you need to protect your brand. You run into a risk where, as you grow, you could lose your leading-edge consumers.

Osborne: Authenticity and credibility are the most difficult to scale, but Brooklyn Brewery did it. Their lager is everywhere, but they still make respected microbrews.

The cannabis industry will grow incrementally until it becomes legal at the federal level. What’s your forecast and strategy for the near future?

Osborne: The near-term scenario is going to be hard for a lot of people, with limited acquirers and limited resources. Some brands are going to get stuck, because there isn’t limitless capital to fund them until there are the right market dynamics for them to get acquired or find other sources of capital.

Heyward: I think branding in the cannabis space has come a long way in a short amount of time as the legitimacy of the market has been established. We’ve evolved from the early days of stoner vibes. Many cannabis brands, retail environments, and even product designs are on par with or exceed what has been happening in other categories of consumer packaged goods. This evolution is fueled by the excitement of something so new and disruptive.

As a category grows, there is always going to be opportunism — people trying to jump on the bandwagon but cutting corners. You need to build a brand on top of a product you can stand behind.

Osborne: The biggest market opportunity is people who are new to cannabis and are more likely turned off by clichéd imagery, claims of potency, and the big weed leaf.

Photos: Courtesy of Red Antler

[…] At its most basic, a company’s or product line’s brand consists of a name, visual identity (logo and packaging), messaging tone, unique selling proposition, and the story of how it came to be and where it […]

[…] difference between failure and success. Whether you are entering the realm of finance, operations, marketing, manufacturing, or investing in a licensed grow, formal training specific to cannabis plants and […]