Bryan Gerber knew nothing about commercial politics and little about the cannabis industry when he began considering the rolling paper industry in 2018. But he was aware of two facts that would prove influential in his future: A global pre-roll cone shortage existed, and pre-roll products were flying off retail shelves across the United States. He trusted his instincts and hopped on a plane with his college roommate to suss out the paper manufacturing scene in India. Within ninety days, Hara Supply’s first cone factory was up and running, and soon thereafter Gerber had a half-million-dollar purchase order in hand from Kush Bottles.

“That first deal funded our first facilities, and it was off to the races from there,” he recalled. “Within three years, we became the largest producer in the world and pretty much took over 30 percent of the market from the other original guys that were [manufacturing papers in] Indonesia.”

Listening to Gerber’s amiable, cerebral conversation style and intermittent laughter as he describes his early success, “cutthroat” isn’t the first descriptor that comes to mind. Over the past decade, he has demonstrated an uncanny knack for identifying and filling gaps in the accessories side of the industry. Since 2018, as the co-founder and chief executive officer at Hara Brands, he has built one of the biggest rolling-paper manufacturing companies on the planet, with fourteen factory operations that produce more than 100 million paper cones a month for some of the biggest brands in the world.

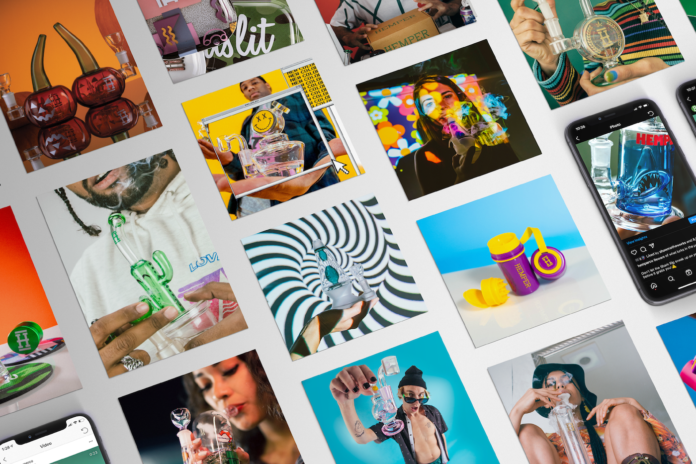

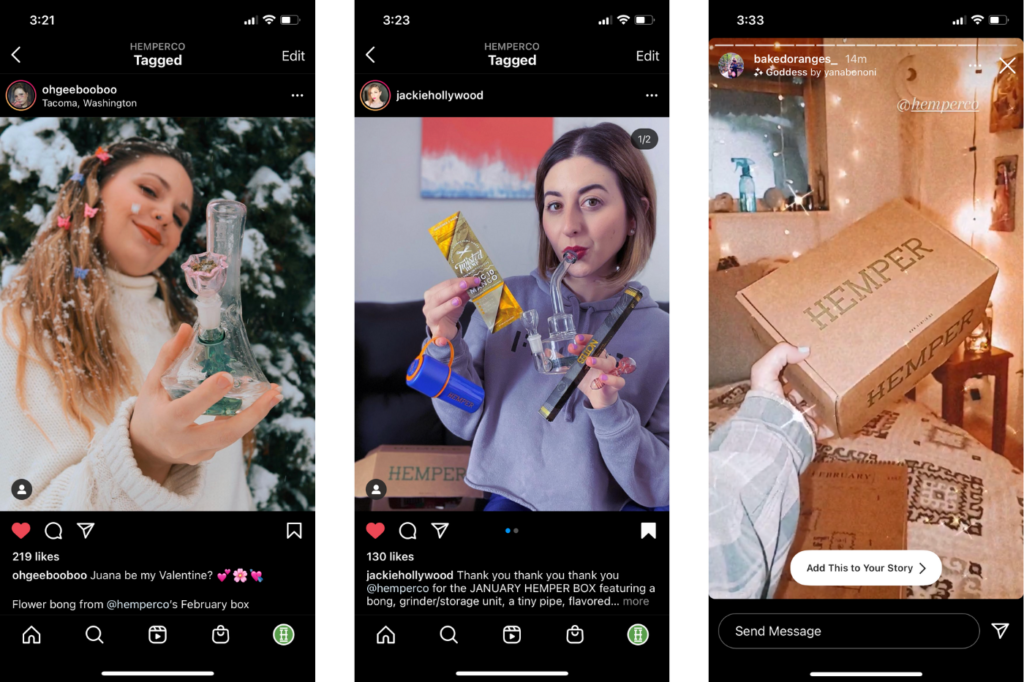

Gerber’s entrepreneurial journey in cannabis started just a week after graduating from college in 2015, when he launched Hemper, a customized subscription box that offered a variety of premium accessories. Three years later, just as he was entering the rolling-paper realm, he consolidated all his operations into Hara Brands, which in the years since has developed more than 300 products and today enjoys more than 30,000 subscribers for its monthly goodies box.

Hara’s business partners have benefited from their relationships with the company, as Gerber’s team has a rare perspective on which products are hot or cooling in each market. As such, Hara is becoming a solutions partner and consultant to consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies, advising them about where and how they might consider expanding their product lines profitably.

In 2024, nearly ten years into his entrepreneurial journey, Gerber seems to be just getting started. His focus this year will be pushing Hara’s products into the massive traditional distribution pipeline that feeds convenience stores and gas stations, working to secure multimillion-dollar deals with mainstream distribution powerhouses like Core-Mark and Eby-Brown. He’s also looking at market opportunities outside the U.S. and wondering just how big he can grow a company that he literally started from an empty box.

“My partners and I are very much the guys who are like, ’Oh, we can get to a $100-million or $200-million or even a billion-dollar valuation,” he said. “There’s nothing special that (the competition) is really doing, and we know the equation; we know the recipe.”

How did you segue from college student into captain of industry?

I went into college as a pre-med major. My dad’s a doctor, so I thought I’d just take over his practice, but I didn’t know what that really meant at the time: overworked and underpaid. So I considered plastic surgery instead. When I told my dad, he said, “Those guys are not doctors. They’re businessmen with good hands. Go into business and make a ton of money, and you’ll save yourself all the nerves and headaches of [medical] school. Just major in accounting. At least you’ll know what a healthy business looks like.”

That advice has served me very well. I majored in accounting and information systems in the business school at [George Washington University]. To be honest, a lot of people try to pull the wool over your eyes in the numbers world, and having that background has been really beneficial.

Your first big business move was the Hemper box. How did you make that such a cultural phenomenon?

The original concept was Dollar Shave Club—sort of a Birchbox for stoners—but then it morphed into something different when I realized one of my competitors was using YouTube to show people unboxing their packages. At that point, I became almost obsessed with conversion-rate optimization and how to drive traffic, and then it became a game. So, instead of having these YouTubers unbox my boxes, I decided to have them curate a box for a month, and that catapulted the subscription to thousands of consumers overnight. I utilized all these small YouTubers, and before long I started working with larger celebrities. We’ve done Cypress Hill collaborations, Flosstradamus, and I’ve done a bunch of others with hip-hop artists—like, “smoke like Snoop Dogg.”

So you’re listening to their music, you’re watching them on TV, and this is just a different way to hang out with them on the couch for thirty days and smoke exactly what or how they’re smoking. Artists got to connect with their fans in a different way; everyone got cool, limited-edition accessories; and everyone was happy.

That was the first sixteen months, and since then we’ve put pretty much everybody’s product in the box. There’s not many more companies left, so I said, “Now what do we do? How do we keep this fresh?” And that’s when I landed on product development being the next key focus.

When did you realize you could grow this cottage business into a bigger thing?

I realized the subscription box was really a Trojan-horse marketing outlet for us to develop our own products. It was like a paid test market, and once we realized we weren’t going to raise hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars to scale this subscription, that’s when things really started unfolding. We were designing products and we released new products on a monthly or bimonthly basis, getting feedback from consumers overnight. So if we could take that data and go to retailers and distributors, then they could sell our products because we’d have a brand following. It was really a data-driven approach to product development.

Did you understand how competitive the paper business is when you started out? Did you bump into any eye-opening moments?

No, I did not know what I was getting into early on, trust me. When I graduated [from college] I needed to make money, so I started diving into all the different categories of rolling papers. When I met [RAW founder] Josh [Kesselman] at my first trade show, he was upset that I put OCB papers in the box next to one of his products. I didn’t know about the [industry] politics at the time. I was so fresh, and all of a sudden I was being told, “You don’t know what you’re getting into, you little kid.”

So then I thought, “What if Hemper had its own rolling papers?” So I started going down the path of [Chinese ecommerce mall] Alibaba. The first dude I found in China, he starts telling me there’s no such thing as rice paper. Within the first six months of starting this business, I realized there was no rice—it was all flax. I was like, “Wait, this [misrepresentation] is crazy. This is all bullshit.” That’s when I realized everything was just brand and story and marketing. And then I started just learning how everyone else was kind of playing the chessboard.

How do you divide your time between the various Hara Brands components?

We’ve got two businesses now. Hara Brands is all the branded CPG stuff, and my focus on that side is more on our initiative for mass-market convenience stores, which we started last year. We’ve been developing new products there more than on the combustible-products side of things: a new take on rolling paper booklets, vendor-package cones, different variations of things. We had this reinvented one-hitter, the Quick Hitter, as well.

I’ve been focusing on getting into Core-Mark and McLane and Eby-Brown and all these other massive mainstream distributors [so we can introduce our products] into 7-11 and Circle K. I’ve focused a lot of my time on that. On the Hara Supply side, I manage a lot of the enterprise accounts, a lot of the [multistate operators] and a lot of the bigger vanity brands. I deal with Zig-Zag and OCB and all these different companies.

How would you describe your business and management style?

“I guess I’m a pretty involved, active CEO, but not in a micromanaging way. I’m more like, “If you can get 70 percent of the noise out of the way and you need help clearing that other 30 percent, I can help you clear that 30 percent very quickly.” I think that’s where you have to figure out how much information you need to make the right decision at the right time.

Raising funds in this industry is super-difficult, and overspending is very common. I’m very risk-preferred, obviously, going into this line of business, but I’m also very conservative. I feel like a lot of people come into this industry and raise a ton of money, overspend, and over-hire. What I’ve realized is that no single employee will ever change or turn the tide for your company. It’s always you, and you have to have a pulse on every aspect of the business. You can’t take your eyes off things. I think that’s a big key. Truly, though, the recipe for success is just passion.

What have you found to be the most impactful marketing strategies?

We took to influencer marketing on social media like Instagram and Facebook pretty quickly. Another method we used successfully was advertising on these massive Facebook groups and Facebook pages. We’re obsessed with growth hacking, so we always find new ways to generate a return without spending much. We blasted through a massive Snapchat network, and now, similarly, there’s massive TikTok networks.

YouTube used to be amazing, but it’s no longer that great. I think the influencer approach we took early on was key to building the Hemper brand, because it generated “social proof,” although I didn’t know what that was at the time. I just thought it would be cool to do a collaboration with some people because they’re famous. [“Social proof” refers to the way people copy the actions of others in an attempt to create behavioral affinity. It’s one of the reasons social media marketing is effective. —Ed.]

We also did a lot of events in the early days, like High Times Cups, Chalice Festivals, things like that.

What advice do you have for making products stand out in crowded market segments?

I really think differentiation in terms of ways to sell a similar vehicle, but getting that extra delta on the price. Maybe adding a glass tip to a pre-roll, for example, or doing whatever else you, as the producer, can do at very little incremental cost. But to the consumer, maybe that little change provides the best experience they’ve ever had. I’d rather sell 50,000 units a year at twenty bucks a pop than a million units a year at $1 a joint.

I think everyone’s trying to figure out what their Coca-Cola is on the shelf. Granted, the legalities don’t make it easy to have consistency across all markets, so that’s an issue. But I think for people who are trying to jump into this or trying to survive, keeping a very tight grip on your cash is vital, because you may never raise another dime again.

I learned that very early on. Luckily, I had great [venture capital] partners who understood the vision and supported us, because, trust me, before I raised a dime there were people out there telling me, “Bryan, I don’t understand what you’re trying to do. Are you a box? Are you a product? What are you?” And I’d say, “If you don’t see the vision, you’re not the right investor.”

I know that now, but I didn’t know that when I was twenty-three years old. I was devastated every time someone said no. But now I realize they just weren’t the right person. So I think three essentials are finding good partners, cash is king, and focus on differentiation with the product.

Do you have any sense of what the next iteration of pre-roll manufacturing might look like? Is another wave of innovation coming?

I don’t think we’ve really seen much innovation yet. I think we’ve seen a lot of repurposed products or technology that’s from other industries that was brought into this one.

I think there are so many efficiencies around the infusion of oil into pre rolls and kief coating. Hundreds of people in a trailer painting kief on a joint? That’s just not efficient.

Everyone’s like, “Oh, we’re entering cannabis 3.0 now.” But I would say we’re in cannabis 1.5 right now. We’re about to break through, but not quite yet. I think over the next probably twenty-four months, we’re going to see some pretty serious innovations come out. [As a consumer,] I want to get to the point where I push a start button, and my product is packaged at the end. And I think a lot of people haven’t figured that out yet.

Do you have any big plans for Hara in the next few years?

I started the business when I was twenty-three, and at thirty-two I definitely have some gas left to keep going. I think for us, really focusing on this mass-market play is paramount. You don’t get to be the size of RAW or something similar by just playing in the smoke-shop world, right? We know that, so we’re really focused on mass-market convenience stores here domestically. That’s a big initiative for us, and also our European expansion. We’ve gotten in pretty heavily there in the past year. We just had a booth at InterTabac, which is one of the largest tobacco shows in Europe.

Bryan Gerber Fast Facts

Age: 32

Birthplace: Maryland

First job: Marble Slab Creamery

Favorite meal: Cheeseburger

Favorite cannabis product: Rosin

Inspiring words: Put good into the world and good things will come back.