Sustainable cannabis cultivation is one of the most complex, charged issues facing today’s industry. As the market continues to mature, companies need to consider the significant environmental impact and massive carbon footprint of energy-intensive operations.

As more states legalize the plant, companies are building indoor production facilities that will add millions of square feet of canopy each year, stretching and straining electrical grids from coast to coast. Meanwhile, greenhouse growers are employing more mixed-light cultivation to produce crops similar in quality to their indoor counterparts, and outdoor growers are struggling to survive as consumers continue to favor frosty, potent buds over organic, full-season flower.

In this context, the notion of “sustainable farming” is difficult to frame or calculate. Nevertheless, regulators, scientists, and farmers are developing new technologies and incentives to help growers become more energy-efficient.

A growing carbon footprint

Some of the biggest indoor cultivation facilities in the United States are located in regions where temperatures reach up to 120ºF in the summer: Las Vegas, Phoenix, and California’s Coachella Valley. Conversely, states like Michigan, Colorado, Massachusetts, and Illinois regularly dip below 0ºF during the winter months. Regardless of where indoor grow rooms are located, they have one thing in common: Optimal temperatures — 65ºF to 75ºF — and precise humidity levels are required to keep plants happy and healthy during their life cycle.

Researchers only recently began to accurately measure emissions and calculate the carbon footprint of cannabis cultivation in both indoor and outdoor settings, but a new study by Colorado State University scientists provides some of the first in-depth data about the issue. The study, published in Nature Sustainability in 2021, used a life-cycle assessment of indoor cannabis operations across the U.S., analyzing the energy and materials required to grow the product and compiling the corresponding greenhouse gas emissions.

The study revealed U.S. indoor cannabis cultivation results in life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of between 2,283 kilograms and 5,184 kilograms of carbon dioxide per kilogram of dried flower. By comparison, greenhouse production without supplemental lighting results in 327 kilograms of carbon dioxide, and outdoor cultivation produces 23 kilograms.

Since California passed Proposition 64 in 2016, massive grow facilities have developed in the state’s southern regions, leading the Coachella Valley to become one of the largest indoor cultivation areas in the U.S. Charlie Kieley, chief operating officer for Coachella-Valley-based Kings Garden Inc., runs a massive facility comprising about 200,000 square feet of production. The operation employs more than 3,000 high-intensity lights.

In an opinion piece Kieley wrote for The Sacramento Bee this summer, he argued indoor cultivators need to convert to LED lights immediately and revealed his company plans to lead by example. “Nobody has all the answers, but in our LED growing trials we are well on our way to defining the methods and formulas for growing high-quality products while reducing electrical load,” he wrote. Kings Garden plans to transition to solely LED lighting before the end of 2022.

In order to reduce strain on the electrical grid, the California Energy Commission has proposed all indoor cannabis operators convert to LED lights by 2023, but it remains to be seen how many growers will follow the agency’s recommendation.

In other legal states, legislators are examining energy use at indoor cultivation sites and developing regulations to limit the impact on electrical grids and the planet. According to a report from the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment, electricity use from cannabis cultivation and other products grew from 1 percent to 4 percent of Denver’s total electricity consumption between 2013 and 2018. In Illinois and Massachusetts, legislatures are putting restrictions on which lighting equipment growers can use, and many utility providers have developed energy-efficiency rebates and incentive programs for growers who install energy-efficient HVAC and lighting upgrades. While natural gas turbines are considered “cleaner” sources of energy than coal-powered plants and can be less expensive to operate, the vast majority of the industry in the U.S. and Canada relies on electrical grids for power.

Regenerative farming

While indoor and greenhouse operations account for most U.S. cannabis cultivation, it wasn’t long ago that outdoor, full-season farms supplied the majority of weed for medical markets on the West Coast. In that context, it’s both ironic and unfortunate these same farmers now struggle to compete against large-scale greenhouses and indoor operations.

Outdoor cultivation now represents just a small percentage of total cannabis production across the U.S., and in some states it isn’t even allowed as a legal means of production. From a sustainability standpoint, however, there is a strong case to be made that outdoor cultivation is the most eco-conscious approach, and growers in Northern California have spent decades perfecting the art of organic farming.

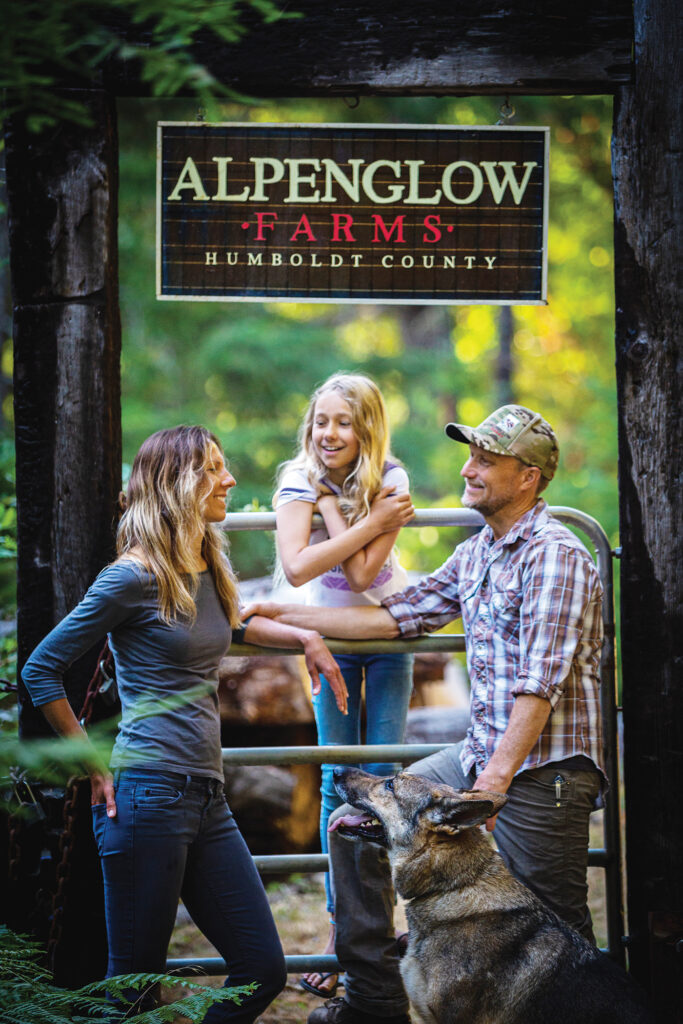

Nestled in the mountains of Southern Humboldt County, California, Alpenglow Farms sits at 1,800 feet on a sunny ridge high above the valley fog. Co-founders Craig and Melanie Johnson have spent the past two decades carving out a homestead and learning how to farm cannabis in the most environmentally sustainable ways possible. Their commitment to “regenerative farming” has earned the farm a DEM (Dragonfly Earth Medicine) Pure certification, which is of the most difficult standards to meet and uphold in Northern California’s sustainable farming movement.

Alpenglow has about 10,000 square feet of production space, of which 7,500 square feet is dedicated to full-season, sun-grown plants rooted directly in the earth from seed. “One of the things that really sets us apart is that in a conventional farm, they would most likely bulldoze [the land] flat, erect greenhouses or put down ground cover, and then water only at the base of the plants, whether it’s a smart pot or a container or some sort of method of containing potting soil,” Craig Johnson said. “That causes a lot of trouble and a lot more work, because water is life. Everything, whether it’s beneficial or a fungus or a pathogen, all of it wants to come to the base of that plant to find water. We really tried to blur the borders of our gardens, and we treat our entire farm as a living biome.”

The farm’s 450,000-gallon rain-catchment pond fills up during the winter and spring and provides enough water for the plants during the dry summer growing season. The homestead is solar-powered, and in the wintertime uses a small hydroelectric system powered by the water flow in nearby creeks.

One of the most efficient and impactful ways farmers can create sustainable farms is through “closed loop” agricultural practices, which continually recycle nutrients and organic matter back into the soil. On Alpenglow’s Instagram page, Melanie posted a video demonstrating how they use cover crops to close multiple loops on the farm. Using raised beds to grow legumes captures nitrogen from the atmosphere, converts it, and stores it in nodules in the soil. The nitrogen-rich soil is then used for cannabis crops; moreover, the legumes provide a ready food source for the chickens on the farm.

Operations like Alpenglow might be a dying breed in California, as industrial-scale greenhouse and indoor facilities lower their cost of production and create more of a commodity market for flower and a steady supply of raw material for companies in the extraction space. Nevertheless, the vast majority of farms in the Emerald Triangle are small craft farms that utilize some form of organic and/or regenerative farming. Their challenge is finding new and persuasive ways to market outdoor flower to consumers who seemingly are hypnotized by the bag appeal and THC levels of indoor buds.

How thirsty is cannabis?

Cannabis growers have been criticized for diverting water from streams and rivers, making a bad drought situation worse on the West Coast. In reality, cannabis requires only a modest amount of water to thrive, particularly when compared to more traditional agricultural crops.

In indoor facilities, a number of technologies help growers capture, treat, and reuse runoff water. “One standard facility for us is about 1,000 lights and 40,000 square feet of operations, and we’re able to capture and clean and treat about 60 percent to 70 percent of our total water demand,” said Kieley. “We’ve drastically offset the amount we need to rely on one of our most precious resources in the desert.”

In October 2020, the Journal of Environmental Management published “Water Storage and Irrigation Practices for Cannabis Drive Seasonal Patterns of Water Extraction and Use in Northern California.” For the report, researchers analyzed data from farmers enrolled in the North Coast Regional Water Board Cannabis Program and found legal outdoor cannabis production uses about the same amount of water per acre as crops like tomatoes.

“Cannabis has a very small footprint and accounts for just a fraction of the water used by California agriculture overall,” said Theodore Grantham, a scientist at the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in California. The authors of the research report concluded they have not “found cannabis to be particularly thirsty relative to other crops… Add it all up and we’ve estimated that a single large almond farm in the Central Valley utilizes thirty-three times more water than all permitted Humboldt [County] cannabis farms combined.”

As the legal industry balloons to a projected $30 billion in sales in 2022, cannabis companies will build more greenhouses and indoor facilities to meet the demand. Hopefully, they’ll prioritize sustainability and energy-efficient technologies as much as market share and profits.

“States like California are doing the right thing by pushing [the industry] to step up and do our part and do the right thing,” said Kieley. “My belief is growers in the industry should be welcoming and openly conversing about these changes as opposed to just being scared and fearful about how to adapt.”

[…] have prioritized flower quality and yield, today’s weed lights are much more likely to factor in energy efficiency and sustainability, especially as the greater industry continues to prioritize these aspects of eco- and […]