Consumers may know the brand, strain, and strength of their favorite vape, topical, or tincture, but they are unlikely to know much about the methods that transform crops into concentrates. This is the realm of extraction artists, and their methods can have as much impact on the product’s effects as the growing conditions that produced the plants.

Technology has given extractors new techniques that often mimic extreme weather conditions: high humidity, dense fog, arctic blasts, high-pressure systems, and sirocco headwinds strong enough to rip the trichomes off a plant. Each method has its adherents, all of whom pursue the same goal: a scalable, cleaner, cheaper, and safer process that yields the purest possible oil.

“Among the rapidly expanding cannabis markets, extraction is arguably the most active area of innovation and growth,” according to a report from Prohibition Partners, which closely monitors the industry in Europe and North America.

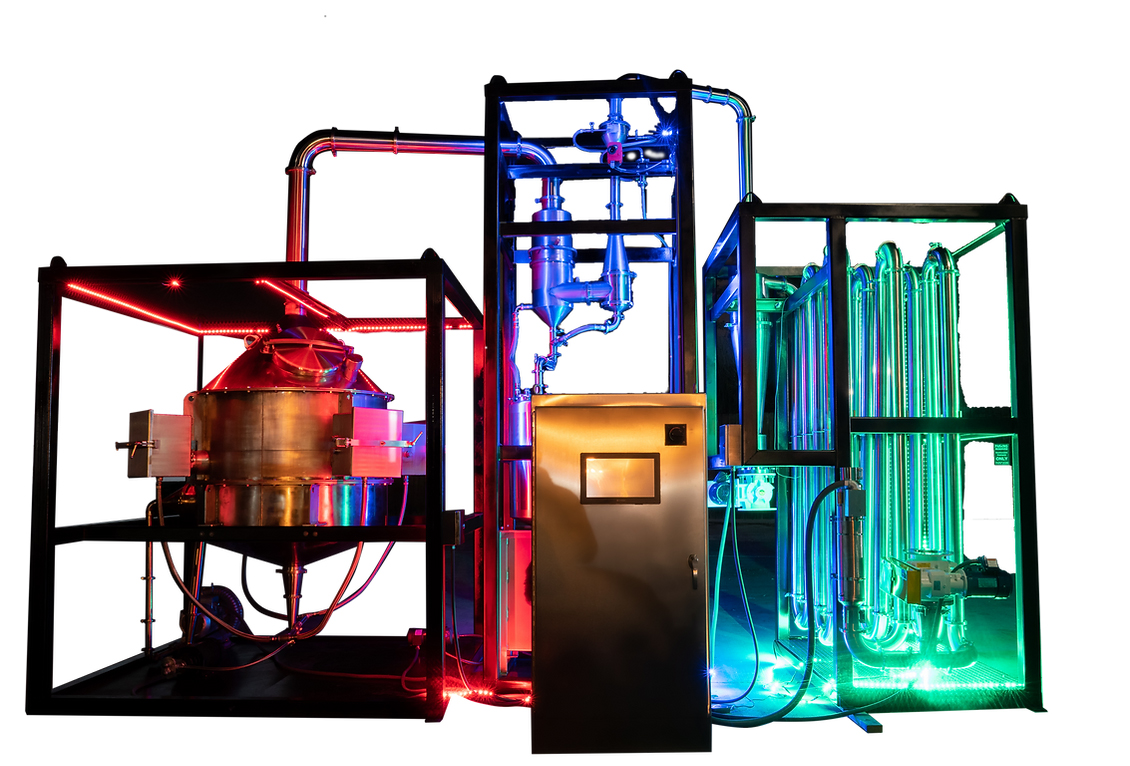

Extraction is an increasingly sophisticated process, and modern cannabis extraction machines are expensive. Most farms and manufacturers still outsource, but others are buying new turnkey systems that allow them to keep the process within their control. In fact, there are so many methods—wiped film, vapor, and vacuum-steam ovens, to name just a few—that competition is spiking in the sector.

At present, much of the competition focuses on economics as equipment manufacturers race to refine technology that will help producers reduce costs in an increasingly challenging market. Demand for cannabis and hemp concentrates has grown in the past three years as more states come online; 90 percent of Americans now have access to some form of legal product. Sales of vape cartridges, which are powerful and discreet, are eating into the market for flower. And anything with “miracle” CBD is off the charts as consumers demand specialized products to treat everything from insomnia and pain to anxiety in people and their pets.

But while consumer adoption is climbing steadily in nearly all legal states, the supply is beginning to outpace the demand in markets where officials are issuing an unlimited number of cultivation licenses and farmers are coaxing higher yields. Wholesale flower prices are falling in some of the largest markets—California, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, among others—and operators across the country are under pressure to cut costs to maintain market share.

To help producers reach efficiency and revenue goals, equipment manufacturers are nudging them away from small-scale lab production toward cheaper and faster industrial systems. G&D Chillers, which served businesses in the beverage alcohol space before engaging with the cannabis industry, has more than three decades of experience working with large-scale extraction operations.

“We’ve got basic economies of scale to consider,” said Scott Timms, G&D’s lead sales engineer. Manufacturers need to “produce more and pay less” per unit.

“We started with some industrials, then distilleries, then craft beer and wine companies,” said Timms, who noted the company’s cannabis business took off when extractors started to recognize the importance of ultra-low temperatures. “We began getting more requests from the cannabis space about five years ago and started moving toward even lower temperatures.” He means really low temperatures, as in -58°F. The company is designing equipment that will bring the temp down to -80°F.

G&D sells specialized equipment to extractors, most of whom find the company on social media and at trade shows. Cannabis is about one-quarter of the company’s business, according to Timms, and the percentage is growing—not least because consumers are discovering the role terpenes play in the effects they experience. The aromatic compounds, which are destroyed by high temperatures, have become the holy grail of cultivation and processing, recognized—but not completely understood—as the plant’s toolkit for taste, health, and beneficial effects.

Sophisticated consumers and researchers are turning to these smaller building blocks to make more focused products. Want to sleep? Look for linalool. Courting couch lock? Myrcene. Suffering from inflammation? Humulene’s got you covered. Each terpene—and there are scores of them—has specific properties affecting a product’s therapeutic value and user experience.

“Extreme chilling preserves desirable terpenes and cannabinoids,” Timms said. “[Our systems] also pull out fats and lipids, chlorophyll, and [other undesirable components] to keep them out of the process.”

Terpenes were just casualties of production until a decade ago, when researchers and growers became interested in the clear, sticky substances. Today, terps are extracted from the plant before it is processed and reintroduced later, like seasoning, to concentrates.

Terplandia is part of a relatively recent trend: the ascent of companies that produce “after-market” terpenes. The company doesn’t manufacture equipment. Instead, it extracts terpenes from industrial hemp and then supplies labs, researchers, commercial formulators, and terpene-obsessed consumers who want to compound their own aromatherapy, concentrates, and edibles. Hemp terpenes are legal in all fifty states because they contain no THC.

According to Terplandia founder Taher Afghani, “There is finally a lot of research on terpenes. We are just beginning to scratch the surface of their health-related, cosmetic, and fragrance benefits.”

Afghani prefers to work directly with farmers. The best practice, he said, is to harvest terpene-laden flowers while the plant is still in the ground—preferably before dawn, when the temperature is still cool. Sticks and stems are discarded immediately, and the flower is delivered into the chamber of Terplandia’s vacuum-steam distillation system. Lowering the pressure in the chamber lowers the temperature needed to create steam, meaning the biomass is processed at roughly one-third the heat usually employed during extraction. The process removes the terpenes from the buds and extracts chlorophyll, waxes, and other unwanted byproducts. The result is run through a mild dryer or spread out in a room with dehumidifiers.

Many extractors use vacuum steam to separate terpenes and cannabinoids from the biomass, but Boulder Creek Technologies isn’t among them. Instead, the company uses a vapor fog. The difference, said cofounder and Chief Executive Officer Rick Bonde, is that cool fog will not degrade delicate components like hot steam can. Boulder Creek’s Vapor-Static system starts with a flash of warm air that is shock-cooled immediately. An electrostatic precipitator pulls out undesirable sugars and waxes by breaking them into droplets and dissolving them into the fog. Because oil and water don’t mix, it is easy enough to separate components in this form.

Bonde said the Vapor-Static system preserves THC, CBD, and other cannabinoids—but not heavy metals or mold—in the oil. “It’s a delicate balance,” he said. “We have to hit the fine balance with temperature and exposure time so we can bring the cannabinoids with minimal damage.” He acknowledged terpenes take a beating.

Many concentrates must be refined a second time to remove solvents and other undesirable components that survive the first pass. Bonde said the extra step is not always necessary with the vapor process. “At this point, other oils are thick and black like motor oil,” he said, whereas Boulder Creek’s process produces a dark amber product. Unlike oils extracted with ethanol or carbon dioxide, he said, Vapor-Static’s oils do not necessarily require a second pass to remove solvents and waxes, a process known as winterizing.

According to Bonde, the oil can go straight into edibles or be further refined for a pale yellow or clear distillate for vape cartridges and other uses. Cutting out the second extraction saves both time and money.

Although most extraction systems have been adapted from those used to produce food ingredients and essential oils, Boulder Creek designed its equipment from scratch to address the specific needs of a specialized industry. “Cannabis is a rapidly evolving technology,” Bonde said. “Rather than perfecting an older tech, we started from the ground up.

The vapor technology is closer to the industrial processes used to trap pollutants before they are emitted from smokestacks, Bonde said. His brother, Steve Bonde, a chemist and Boulder Creek’s chief technology officer, spent nearly three years developing the system, primarily in response to a schism over the use of solvents, which are efficient and effective agents for separating cannabis components but also may trigger environmental and health concerns.

Extraction often relies on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) including ethanol and hydrocarbons like butane, propane, and hexane to separate terpenes and cannabinoids from wax, sugars, and other waste materials that may affect the final product’s properties. Carbon dioxide, also considered a solvent in its liquid form, is non-flammable and non-toxic. Some extractors consider it a safer alternative, not only for products intended for human consumption but also for extraction workers. Methods using solvents currently are the most common extraction techniques, and proponents say the elements are not harmful if they are used properly and the final product is cleaned well. Lab tests mandated by state regulations are supposed to prevent unsafe levels of VOCs from creeping into the supply chain. Solvents usually are purged in a secondary run, a process some complain further degrades the desirable components of the plant or leaches potency.

Boulder Creek’s electrostatic precipitator eliminated the need for solvents. “We knew we had to go solventless,” said Rick Bonde. “Consumers are starting to demand it.”

Pro-solvent extractors say their processes produce a more potent product that retains most of a flower strain’s flavor at a lower cost than solventless systems can offer. Butane hash oil, or BHO, extraction is preferred by many large-scale extractors because the systems are scalable and versatile.

“Solvents aren’t necessarily bad if they are pure and properly used,” said Ben Britton, CEO and director of development for PurePressure, a division of agricultural technology corporation Agrify. “But when consumers start to think about solvents and additives, they don’t want them.” This is particularly true of sophisticated customers who don’t mind paying more for the products they consume. An extract produced without solvents commands the “highest price on the shelf,” said Britton, whose company specializes in solventless technology. PurePressure’s sister company, Precision Extraction, manufactures BHO extraction equipment. “It’s important to know where your market is.”