In successfully bringing the city and the industry together to finally fix the cannabis industry in Los Angeles, Virgil Grant has been able to do what no one before him could accomplish.

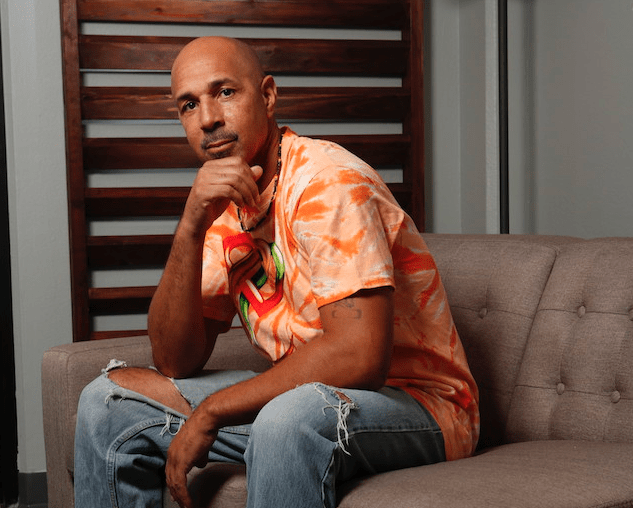

At 49, Compton-born Virgil Grant looks like he still could run the 400-meter dash and the 300-meter hurdle, and win, just like he did as a star athlete at Lynwood High back in the day. Lean and muscular, he projects a quiet concentration common to good runners. The formidable mix of determination and calm serves him well as he tries to bring together a squabbling and fearful industry in a last-ditch effort to save its future. That is the challenge Grant has placed on his own shoulders: to wrangle, tame, and then redirect the energies of all cannabis industry stakeholders in the largest market in the world—Los Angeles—for the betterment of the industry, its patients, the entire city, the state, the nation, and the world.

The effort may seem impossible for a single individual, but Grant is not an average individual. His is an epic tale about a man living a fearless and principled life; working his way up to become the cannabis king of Compton, the operator of the only six legal medical marijuana collectives south of Interstate 10, and a felon whose most recent case landed him in federal prison for six years on cannabis-related charges. His sacrifices and achievements have made Grant a legend in the industry, but his outlook on life prevents him from resting on any laurels he may have gained. Instead, he has returned with a vengeance—not to seek revenge but to pick up where he left off.

“One thing I was determined about was to not let them drive me out of this industry,” he said in mid-October. “That was a determining factor in me coming back stronger than ever. I wasn’t going to let them take my finger off the pulse of this industry that I had been in for years. I had six shops when nobody in Los Angeles had multiple shops except for The Farmacy. There was no way I was going to go away.”

“I didn’t ask [the city council] to do something. I demanded that every one of them get off their butt and do this the right way. We have to make sure the number-one market in the world is fixed, because it’s broken and the world is watching.” —Virgil Grant

The Early Days

Grant is straightforward when talking about cannabis. There is nothing about the industry he does not know, but those who knew him as a kid probably never have envisioned such a future.

“I was diagnosed with ADHD, but my dad would not allow them to medicate me,” he recalled. “He told my mom to put me in sports and let it burn off, and that’s what they did. I played Pop Warner football and Little League baseball. In high school, I ran track. My mom sent me to Lynwood High because she didn’t want me to go to the schools in Compton because of the gangs.

“At Lynwood, most students were athletes,” he added. “Everyone came out of there with a scholarship, because we were filled with talent. I was the number-one track athlete at Lynwood and came out with a scholarship to San Diego State University.”

It was not to be. “My dad owned five liquor stores in Compton, but was going through some issues with people working for him who were stealing him blind. I made the decision to do what they call a scholarship swap and ended up going to Cal State, Los Angeles, instead of San Diego State, because it was closer and I could help in the liquor stores. I started working the night shift from 4 p.m. until 2 a.m., overseeing two of the stores.

Rastas

An athlete, Grant did not use drugs of any kind. He was introduced to weed through the liquor store, which he had transformed from an old-school shop into a reflection of contemporary culture. “I was always into my culture,” he explained. “I sold T-shirts with Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey on them and always had incense in the store. It was in a predominantly Crip [gang] neighborhood but in neutral territory, so I set the tone early. I played a lot of Reggae, wore my beads, and sold a lot of incense and oils. I was a hippie sort of guy, and that’s how I was perceived within the community, as a righteous brother.”

Dannylocks, Jamaican construction worker from a project across the street, would stop by daily. “He would come by and we would talk,” said Grant. “One day he pulls out a leaf and starts rolling his herb in it. I asked what it was and he said it was a blunt, that the leaf would blunt the smell of the herb. Later on, I found out he had a known weed spot in Watts near Nickerson Gardens. I knew a lot of people on that side of town, so he extended an invitation to me. I told him it was not my thing, and we left it at that. I started thinking about it, and ended up cashing one of my checks and buying some weed from him. I guess I got into it for the culture, me loving Reggae, healing the world, and all of that.”

His career in cannabis had begun. “I bought my first weed, bagged it up, and went about strategically picking people who came through the store who I knew smoked and would keep things lowkey. That was how I got started. I took that money and bought more. From then on, I could never buy the same amount. I would have to buy more. I needed to see my money working for me.”

Selling $20 bags eventually didn’t cut it. “I was now buying quarter pounds, half pounds, and pounds,” he said. “I was no street dealer, but I wanted the streets to have my product. So, how could I make that happen? Well, I knew everyone in the neighborhood and they knew me.

“This was my thought,” he added. “In King of New York, Frank White says at one point, ‘If a nickel bag is sold in Central Park, I want in.’ I said, ‘If a nickel bag is sold in Compton, I want in.’

“Long story short, I found out who was running the spots, gave them samples, and they all called me back immediately. I took over Compton like that, and three projects in Watts the same way. At this point, I’m running the city.” That was in 1991-2, long before the legalization movement took shape.

Grant had been getting his weed from his original source for a long time, but as his enterprise grew, he needed cheaper and more direct sources, even if he had to travel upstate to find them. He used the opportunity to visit the Reggae on the River event to find his own Humboldt connection, and soon became the farm’s only customer. “I’m driving up there twice a week instead of once,” he recalled. “It’s all me. I go up to Humboldt to get my weed by myself, and come back down and sell it by myself. And I’m still working day and night at my daddy’s liquor store.”

America’s War on People of Color

Then fate, in the form of government oppression, intervened. “I did two terms in prison,” Grant said. “One in 1997: fourteen months, twenty days in state prison on cannabis-related charges. Two nickel bags. Possession for sale.” Felonies, even though most people got probation or drug-diversion programs for similar busts. “First case ever in my life,” said Grant, his famous cool fraying a bit. “I had never had a traffic ticket, never been stopped. Ever.”

He got out on parole in 1998 and soon was pulled over while transporting six pounds from Humboldt to LA. The court was cavalier about the charges. “They laughed at me,” said Grant. “Six pounds in Mendo[cino] is like an ounce of weed, so they kicked it back to the parole board, which gave me a year flat. I went from Mendocino County jail to San Quentin, and after a few months to fire camp again.” [Fire camps are groups of prisoners trained to fight wildfires.]

Released again in 1999, he had to re-start his operation from scratch. “I had a little bit of money, enough to get started, and I jumped back into working for my dad in the liquor store and for myself on the street,” Grant said. “Boy, were people happy to see me back.”

Retail

The only dispensary in Los Angeles at that time was The Yellow House in West Hollywood. Before long, Grant started thinking about opening his own place. “I’m getting tired of [selling] on the streets,” he said. “I was reading up, doing my research, and doing patient advocacy. A few more shops open and I go visit them. I also get my recommendation and purchase some herb. I’m still not smoking, but I’m figuring it out.”

In 2004, he opened Holistic Caregivers in Compton. “I got these two guys and said I wanted to do it. I took the white guy down to the city to get the license. I couldn’t have my face up there, so we put him in as the front man. We get the corporation, and I do all the paperwork. I know what needs to be done. No lawyer, either. I’m doing everything on my own.

“But my partners don’t want to work in the shop,” he continued. “They’re scared, so now I’m the only one working. I’m receptionist, security, and budtender. I also told my connection up north that now I needed different types of weed, every type of strain, all the product I can get.”

Even sleep-deprived, Grant operated the collective with the kind of efficiency that breeds almost immediate success. “It got to the point where I had to hire someone for the back, because it was time for me to open another shop in Gardena—the first one to be licensed in the city,” he said. “Then someone turned me on to a lease in Crenshaw. I got a license from L.A. and opened on Crenshaw Boulevard, doing the same thing I did in the Compton shop, running it by myself.”

The process repeated itself. Soon, he was running five collectives. “Then there’s a dude in the Valley hurting bad and needs help,” Grant recalled. “I save him and take a percentage of the business, and now I’ve got six locations.”

All the shops operated in the same way. “I sold everything: flower, edibles, concentrates, made my own hash, and made my own teas,” he said. His vision from years earlier was coming true. “When the opportunity opened for me to get into a shop so I didn’t have to street deal, I took it, but look what I walked away from. $20,000 every two days to open a shop and make $300 my third or fourth day in business.”

The Raid

Grant purchased 133 acres in Humboldt in 2006 and cultivated for two years, but by 2008 he was being targeted by the feds in a trumped-up case that reeks to this day. On May 27, 2008, Drug Enforcement Administration agents raided one of his dispensaries, arrested him, and indicted him on forty-one counts of drug conspiracy, money laundering, and operating drug-related premises within 1,000 feet of a school. When Grant insisted on fighting the charges, prosecutors went after his wife.

“She had never worked a day in the place,” he said. “They got her because she would fill out checks to pay bills, which I would then sign. When they pulled her in and went to the trouble of hiring a handwriting expert, I had a decision to make and took what is called an open plea, because I have five kids and can’t risk both of us. An open plea means the judge will decide how much time you get. It’s a gamble.”

Charges were dismissed against his wife, and Grant was sentenced to six years in prison on March 22, 2010. He was released January 23, 2015.

Back in LA

Grant is a self-contained individual, very intelligent and extremely self-assured, but he admitted he spent a few bitter years in prison. “I was mad at everything, the system, everybody that didn’t support me like I had been there for everybody else when I was doing well. I gave to a lot of people, and I did a lot for my community.” A strong believer in “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” he insists his time in prison didn’t change him. “It changed the way my family perceives the industry, but it didn’t change me,” he said. “I’m not going to allow any circumstances or situations I go through to change me as an individual.”

Neither is he the type to whitewash what he sees, and what he saw when he returned was a Los Angeles cannabis industry in disarray. Factions fighting among themselves, unable to lobby effectively with one cohesive voice, made it impossible for the city council to deal efficiently with the industry. Grant could have stayed out of the fray, rebuilt his own businesses and eventually reaped the rewards of a pre-ICO license, but that is not Virgil Grant.

Committed to a unified Los Angeles cannabis industry he all but founded, Grant doubled down with both his colleagues and the city. “People respect my position in this industry because of how long I’ve been in and the price I’ve paid,” he said. “Everybody knows that story and respects it.

“I called all of them to the table one day and asked if they would consider what I had to say,” he continued. “They had enough respect for me to all come. I gave them the story and the history of this industry and how we’re going to survive, but we’ve got to do it together. This industry has been fragmented for a long time, but banded together we can fight off big business, because they’re coming. Seven to ten years, and they’re going to be here. This is the number-one market in the world, but [corporate giants] cannot control it unless we give them control.”

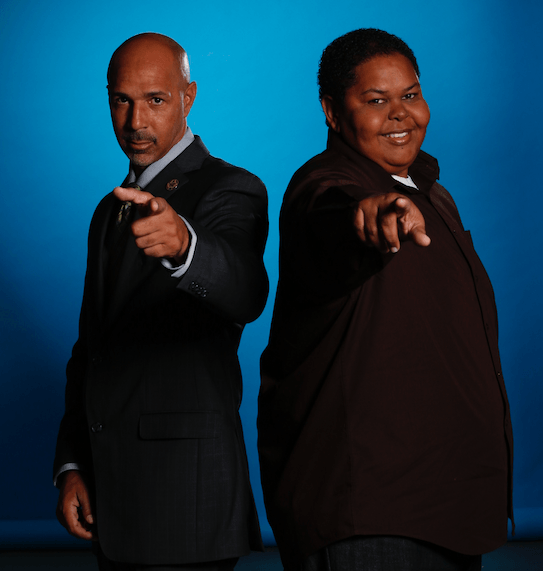

The Coalition

The Southern California Coalition, an umbrella group formed by Grant, Donnie Anderson, and other local business owners, henceforth will represent the cannabis industry in talks with Los Angeles. Committed industry leaders representing all sectors of the industry compose its newly formed board. Convincing a group of passionate and vested people to set their egos aside and come together wasn’t easy. “You have to take charge, which is what I did with the Coalition,” Grant said. “I let everybody know we’re running this. The Coalition is running this. You want something in L.A.? Come see us about it. You want the ear of the city council? Come see us about it.”

To follow through on that promise, Grant and Anderson had to gain the trust of the Los Angeles City Council, a group of hardcore politicians notorious for their reluctance to fix the cannabis industry in their own city. Amazingly, in meetings with the city council over the past, Grant has managed to do just that. “This is what I said to every city council member I met with,” he said. “I left them with this: There is no more do-over; it must get done right now. The world is looking at us to see what we are going to make. It all starts right here.

“I didn’t ask them to do something,” he continued. “I demanded that every one of them get off their butt and do this the right way. We are the working group that will help you make this right. We have all the working knowledge of this industry and will help, but we have to make sure the number-one market in the world is fixed, because it’s broken and the world is watching. It depends on you, and you, and you, and everyone in this room. That’s the conversation I had with every city council member.”

The conversations apparently worked. The council, in collaboration with the Southern California Coalition, will host a series of town hall meetings in November to begin the process of determining “how best to regulate all aspects of the marijuana, or cannabis, industry within the city of Los Angeles.” Henceforth, the coalition’s working group and the council will work together to draft a 2017 ballot measure that will have the support of both the city and the industry. Cooperation has developed much sooner than veteran observer thought it would, and the lion’s share of credit goes to one man.

“Like a lot of people, we’ve been trying to figure out how to unify the industry,” said Eric Hultstrom, founder of the Los Angeles Cultivators Alliance. “When I saw Virgil at one of our meetings about seven months ago, I got very excited, because if there is one person who can organize this industry, it’s Virgil. He’s a hero and martyr to the movement, and there is virtually nothing anyone can say to him. When Virgil talks, people listen.

Everyone “knows what he went through, why he went through it, and who he went through it for,” Hultstrom continued. “How can you argue when he calls for unification, working for the greater good, and building something better? Back in the day, we were all fighting for a movement, but over time a lot of people stopped focusing on why we were here, which was for the patients. I think Virgil coming back reminds people why we were here in the first place and what we need to get back to. He’s the glue that’s held us together.

“I have done plenty of lobbying with Virgil at city hall,” he added. “What he did was bring back into focus issues that are more relevant to the greater paradigm, even for the councilmembers, like minority ownership and representation in the city. It also makes sense to them to regulate the entire industry rather than a small group, and tell them they can get permits and we’ll figure out everything later.”

Todd Hill, operator of the Buddhii cooperative and delivery service, commented, “Definitely Virgil has been an integral and necessary catalyst for finding common ground among all these disparate groups, half of whom, frankly, are still operating illicitly. He has been able to unite the most professional, high-caliber individuals who really are committed to stepping out of the gray market and embracing a fully regulated and compliant industry. It’s a testament to Virgil’s vision and, quite frankly, I think he understands what will be required to move forward in a very special way. He has been willing to elevate himself, and has been very good at understanding the caliber and character of the people who need to be at the table, to make sure that when we are sitting with [L.A. City Council President] Herb Wesson’s office, the voices at the table are ones no one can dismiss.”

California Minority Alliance

Grant and Anderson also recently founded the California Minority Alliance as a necessary component of the big-picture changes they want to see in Los Angeles and beyond. The alliance will have a voice in the coalition, representing minority interests, but its primary mission is mentorship, helping newcomers to become successful and responsible members of the industry. The alliance also will find and direct the necessary resources to ensure more minority-owned businesses serve the people of Los Angeles, especially the communities that have been traumatized for too long by the so-called war on drugs.

The organization “was founded in January, and we have 236 members right now,” said Anderson. “People who are part of the California Minority Alliance are Asians, Native Americans, Hispanics.”

Grant added, “Something I’ve been very aware from day one is that out of the 187 collectives that are pre-ICO, there are only three African-American owners. My thing is to make sure I hold open the door that I have been allowed to walk through for my people to get in. If I can educate enough of them to understand how important it is to get on this and make it happen so they can help lift other people within our community, it’s all part of my vision moving forward.”

As if they do not have enough to do, Grant and Anderson have partnered in his parent company, which they renamed California Cannabis. They’ve pared the business down from six shops to three, with another opening imminently. As with everything else he does, Grant is very excited about the future of his business, especially because he is in line to receive one of the state’s coveted 10A licenses allowing vertical integration, including the operation of a lab.

“California Cannabis is going to run the industry, because it is a marketable, recognizable name,” said Grant. “I don’t have to spend a lot to market it, because the name speaks for itself. Now you can get what you’ve always wanted: California cannabis.

“We are working with a city now to get licensed in that city for cultivation, manufacturing, distribution, and transportation,” he added. “If we are successful in that, and we are going to be, it sets us forever.”

Into the Future

Grant’s eye is always on the future even as he tills today’s soil in preparation for tomorrow’s crops. A complex man able to simplify complicated concepts, he offers a straightforward formula for keeping the LA cannabis market above ground. “We soften the number of shops—134 cannot be it—and we have to have sensible regulations, a licensing scheme, and proper enforcement,” he said. “[Alcoholic Beverage Control] has done it, so we can do it.”

He’s also considered what continues to motivate him to take a leadership role in the industry. “Let me explain something to you,” he said. “There are people who say they believe in what they do, and then there are people who believe in what they do. Martin Luther King believed in what he did. Malcolm X believed in what he did. These are people who were willing to go all the way for what they believed in.

“I believe in medical cannabis. I believe in it,” he continued. “I could have stayed in the streets and clocked my twenty to thirty grand every two days and not even be seen. When the feds hit me, I could have sold each shop, six shops, a couple of million apiece, and walked. I would have been okay. But I stand for what I believe in and don’t bow my head to no one for no reason. I feel like I paid my dues, and now I’m owed something.”